Background: universal design and creating supportive early learning and care settings

Figure 2. Bernie’s Pre-school, Knockainey, County Limerick

2.1 Universal Design Introduction

The term Universal Design (UD) was first coined by Mace (1998) to refer to “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, within the need for adaptation or specialist design”. In Ireland, the Centre for Excellence in Universal Design (CEUD) at the National Disability Authority (NDA) refers to UD as “the design and composition of an environment so that it can be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible by all people, regardless of age, size, ability or disability”.1

1The definition adopted by the CEUD draws on the Disability Act 2005, which defines Universal Design as meaning: “the design and composition of an environment so that it may be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible, in the most independent and natural manner possible, in the widest possible range of situations, and without the need for adaptation, modification, assistive devices or specialised solutions, by persons of any age or size or having any particular physical, sensory, mental health or intellectual ability or disability.”

In a similar vein, the definition of UD adopted by the United Nations in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD, 2006) refers to ‘environments ... to be usable by people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialised design’.

UD is not only about removing barriers but also about creating the right environmental conditions for social inclusion across all human abilities. Human abilities, as defined by CEN–CENELEC (2014) include; physical abilities, sensory abilities, and cognitive abilities, and these vary from person to person and change as a person gets older. Sanford (2012) also discusses human abilities, breaking these down in a similar manner except describing abilities as: motor abilities (similar to physical abilities), sensation and perception abilities (in part similar to sensory abilities), mental abilities (as above), and communication abilities. The inclusion of perception above takes account of how sensory information is perceived or processed, not just received. The addition of communication abilities is particularly relevant in the educational context and here Sanford includes speaking, writing, reading, listening, conversing, using social cues and regulating emotions, along with other similar communication abilities.

“Universal design is intended to engender both positive activity and participation outcomes by focusing on all abilities of all individuals rather than on people with disabilities alone. As a result, universal design is not just about access for some, but it is about usability and inclusion for all.”

(Sanford, 2012.p.xiii)

In this regard UD moves beyond the issue of physical accessibility and promotes an integrated approach which is reflected in the design goals and design principles outlined later in this chapter and captured above in CEUD’s definition of UD which focuses on environments that can “...be accessed, understood and used to the greatest extent possible.” These domains of accessibility, understanding, and usability are discussed below. Accessibility is largely associated with physical (or motor abilities), sensory (sensation abilities), or age and size, and must not only address access within the ELC building, but also ease of access to the setting; Can users easily get from their home to the ELC setting; as pedestrians, cyclists, via public transport, or by private vehicle?

Understanding is principally concerned with mental abilities, sensory abilities, perception abilities (as outlined by Sanford) and communication abilities. UD in this context must cater to a variety of users in terms of intellect, cognition, learning, and memory. Among other things, aural and visual messages must be easily understood, signage must be intuitive, and wayfinding around any environment must be simple and easy to follow.

“People of diverse abilities should be able to use buildings and places comfortably and safely, as far as possible without special assistance. People should be able to find their way easily, understand how to use building facilities such as intercoms or lifts, and know what is a pedestrian facility and where they may encounter traffic.”

(CEUD, 2014a)

Usability must look at how design increases the ‘usability range’ (Balaram, 2011) to foster inclusion and equality. Balaram argues that the “usability range of any product or service will increase once we view universal design as more than mere access” (p.3.5). In discussing usability, Sanford (2012) looks at human function and functionality. Function refers to human abilities (as outlined above), while functionality includes usability and is the interaction of human function and physical forms.

“Functionality is usability and inclusivity of physical form that enable engagement in activities/tasks and participation in society and societal roles. Functionality is a product of the interaction between demands exerted by physical form and human function.”

(p. 6)

Usability, and the resulting functionality of products or services, is therefore determined by how well a design caters for the full range of human abilities: motor, sensation and perception, and communication abilities. As the interaction of human function and physical form, usability is in many ways the combination of accessibility and understanding.

The UD approach advanced by CEUD offers an integrated understanding of UD which includes a UD philosophy, the UD principles, a UD process, and the concept of personalisation. The UD philosophy proposes that people should be enabled to participate in a society that takes account of human difference and should be able to interact with their environment to the best of their ability. Personalisation allows enough flexibility and adaptability in a design to facilitate a level of specialisation, should it be required, to suit individual needs. Personalisation also refers to a participatory process as it is about users shaping public services, including education.

“Personalisation is …about putting citizens at the heart of public services and enabling them to have a say in the design and improvement of the organisations that serve them. In education this can be understood as personalised learning - the drive to tailor education to individual need, interest and aptitude so as to fulfill every young person’s potential.”

(DfES (UK), 2004.p.4)

2.2 Inclusive Pre-School Education: Recent Developments in Ireland

Underpinned by a government commitment, influenced by research on the efficacy of Early Learning and Care and the core principles of human rights; social justice and equality of opportunity, ELC in Ireland has undergone a seismic transformation in recent years, culminating in the National Childcare Scheme announced in 2016 and First 5 - A Whole-of-Government Strategy for Babies, Young Children and their Families 2019 – 2028 launched in 2018. The key policy developments, and how these influenced the development of the Universal Design Guidelines for ELC settings are outlined below:

Better Outcomes, Brighter Futures (Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA, 2014: 5) highlights in Outcome 2 of the five National Outcomes, “That all children are achieving their full potential in all areas of learning and development”. Access, in its broadest sense, is key to this. Ensuring quality services is named as one of the six transformational goals for achieving the national outcomes. The development of the Universal Design Guidelines for ELC settings will support these aspirations and help in their becoming a reality for all children, parents and educators.

Síolta, the National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education (CECDE, 2006) provided a structure to guide the Literature Review on which the Universal Design Guidelines are partly based. Síolta (ibid: 6), in the first of twelve principles, The Value of Early Childhood, outlines the need for “early childhood to be nurtured, respected, valued and supported in its own right”.

The other principles include Children First, Parents, Relationships, Equality, Diversity, Environments, Welfare, Role of the Adult, Teamwork, Pedagogy and Play.

Síolta, is underpinned by sixteen standards of quality which define quality practice within the framework. The breadth of the sixteen Síolta standards is very wide and for the purposes of the development of the UD Guidelines for ELC Settings we focused on seven, namely:

- Standard One: Rights of the Child

- Standard Two: Environments

- Standard Three: Parents and Families

- Standard Five: Interactions

- Standard Six: Play

- Standard Eleven: Professional Practice

- Standard Sixteen: Community Involvement

Síolta acknowledges that the 16 quality standards are inextricably linked and the framework is designed to encourage cross-referencing between individual standards (CECDE, 2006). Consequently, while all standards are not explicitly addressed, the review of key pedagogical and care issues for ELC settings, is aligned with the definition of quality presented across all sixteen standards. Given the nature of this review, Standard two, Environments, is seen as underpinning the discussion on the seven selected standards. Moreover, Standard nine Health and Welfare is reinforced throughout Chapter three with emphasis placed on children’s needs for a physically and emotionally safe and secure early learning environment.

The seven selected standards of quality reflect the European Key Principles of a Quality Framework (Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission, 2014: 8). The European Framework says “In all Member States the following transversal issues are fundamental to the development and maintenance of high quality ECEC (Early Childhood Education and Care) and underpin each statement in this proposal:

a clear image and voice of the child and childhood should be valued. Parents

are the most important partners and their participation is essential in a shared

understanding of quality”.

The key links in the European Framework that fuse with the Universal Design Guidelines for ELC settings are:

- provision that encourages participation, strengthens social inclusion and embraces diversity.

- supportive working conditions including professional leadership which creates opportunities for observation, reflection, planning, teamwork and cooperation with parents.

- a curriculum based on pedagogic goals, values and approaches which enable children to reach their full potential in a holistic way.

Aistear, the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA, 2009) is the curriculum framework for children from birth to six years in Ireland. The purpose of Aistear is to provide information for adults to support them in planning and providing enjoyable and challenging learning experiences to enable all children to grow and develop as competent and confident learners. It also has twelve principles, presented in three groups. These twelve principles intersect with Síolta and the European Principles in the areas of Environments, Play, Equality and Diversity and Parents Family and Community.

The Aistear Síolta Practice Guide (NCCA, 2015) links the principles of Síolta and Aistear, in the Curriculum Foundations section (www.aistearsiolta.ie).

Department of Education Guide to Early Years Education (EYEI) focused inspections. (DES 2018)

In 2016, the Department of Education and Skills published this framework to guide their inspections of settings proving the universal pre-school programme (ECCE). It is based on Aistear and Síolta. The Guide to the EYEI can be downloaded at: https://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/Evaluation-Reports-Guidelines/guide-to-early-years-education-inspections.pdf

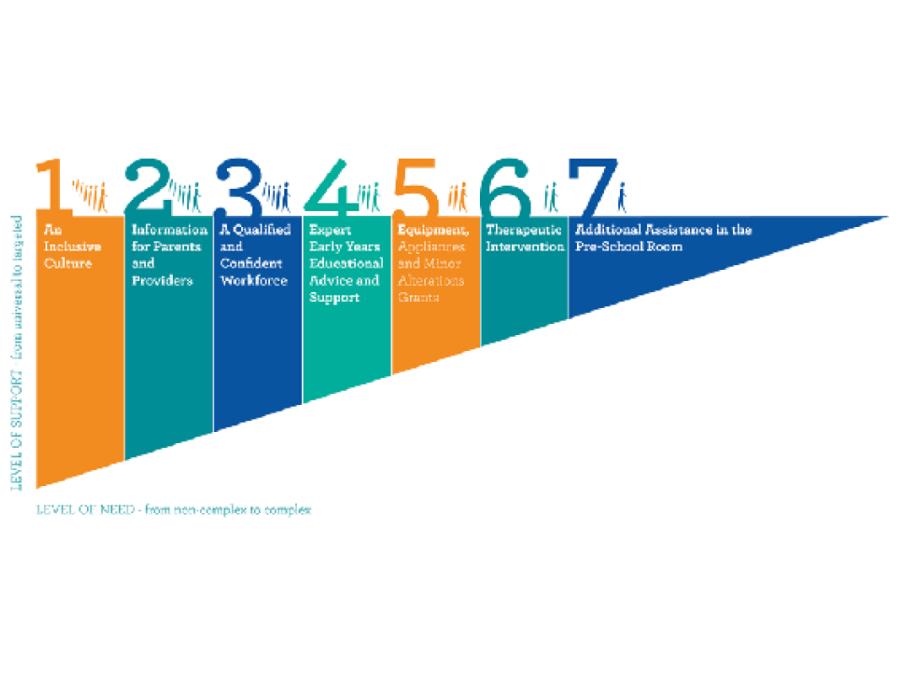

The Access and Inclusion Model (AIM) was launched in 2016. It is a model of supports designed to ensure that children with disabilities can access the Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) programme. Its goal is to empower pre- school providers to deliver an inclusive pre-school experience, ensuring that every eligible child can meaningfully participate in the ECCE Programme and reap the benefits of quality ELC.

AIM is a child-centred model, involving seven levels of progressive support, moving from the universal to the targeted, based on the needs of the child and the pre-school service (see Figure 3). For many children, the universal supports offered under the model will be sufficient. For others, one particular discrete support may be required to enable participation in the Universal pre-shool programme, such as access to a piece of specialised equipment. For a small number, a suite of different services and supports may be necessary. In other words, the model is designed to be responsive to the needs of each individual child in the context of their pre-school setting. It offers tailored, practical supports based on need and does not require a formal diagnosis of disability (www.aim.gov.ie).

Figure 3. A Model to Support Access to the ECCE Programme for Children with a Disability

The introduction of the AIM, with its focus on enabling access to ELC for all children further represents the commitment by government to supporting universal access for all children, irrespective of need or ability (Inter-Departmental Group (IDG), 2015).

In 2016 the launch of the ‘Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Charter and Guidelines for Early Childhood Care and Education ’ by the DCYA, saw a major step forward for inclusive ELC in Ireland. According to the DCYA the aim of the charter and guidelines is “...to support and empower those working in the sector to explore, understand and develop inclusive practices for the benefit of children, their families and wider society.” And to promote “...the values of diversity, equality and inclusion for all children attending early childhood services (XI).”

Furthermore, the guidelines acknowledge the role of the physical environment and the importance of a setting that “is accessible, diverse and inclusive to all children, families and early childhood practitioners.” This is particularly relevant to this review and this section of the DCYA guidelines will be examined later on in this report.

The Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations (DCYA, 2016) set out the minimum criteria that must be complied with by registered early years services in Ireland. This includes services across the spectrum from purpose-built stand-alone-settings, to services attached to private dwellings, and also childminding services provided within the childminders’ private residence.

These regulations cover eight key areas including: Registration; Management and Staff; Information and Records; Care of Child in Pre-School Service; Safety; Premises and Space Requirements; Notifications and Complaints; and Inspection and Enforcement.

In the context of the built environment, a number of these areas refer to specific minimum spatial and design requirements that must be complied with by all registered early years services. The Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016 can be accessed https://www.dcya.gov.ie/docs/Child_Care_Act_1991_(Early_Years_Services)_Regulations_2016_/3780.htm

The Early Years Inspectorate within Tusla, the Child and Family Agency, is tasked with implementing the Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016, and with supporting services to comply with these regulations. To achieve this the Inspectorate has devised a Quality and Regulatory Framework (QRF) that sets out the core regulatory requirements of the regulations and provides supporting documentation such as best practice guidelines or samples and templates for setting-based policies and procedures.

The Early Years Inspectorate conducts pre-school inspections to monitor the sector and ensure settings are striving towards full compliance with the regulations. The Quality and Regulatory Framework can be accessed https://www.tusla.ie/services/preschool-services/early-years-quality-and-regulatory-framework/

Recent initiatives such as the ‘Demonstration Project for In School and In Early Years Therapies’ illustrate the potential for greater collaboration between ELC practitioners, therapists, and parents in many ELC settings (Department of Education and Skills (IRL), 2018). This pilot, developed by the DES, DCYA and Department of Health (DoH) is co-ordinated by the National Council for Special Education (NCSE), will include:

- Early intervention and tailored supports.

- Bringing specialised therapists into schools and pre-schools to provide tailored support to children.

- Collaboration and greater linkages between therapists, parents, teachers and other school and pre-school staff.

- Developing greater linkages between educational and therapy supports.

- Providing professional training and guidance for school and pre-school staff and parents in supporting children’s therapy and developmental needs.

- Maximising the participation of parents in their children’s communication

development.

While this initiative is at an early stage, it suggests a wider role for an ELC setting within the community and the need for settings to facilitate onsite meetings and collaborative sessions between staff, therapists, parents, and various stakeholders.

Finally, First 5 - A Whole-of-Government Strategy for Babies, Young Children and their Families 2019 – 2028 (Government of Ireland, 2018) was launched in late 2018. This is a ten-year cross-Departmental strategy to support babies, young children and their families aimed at delivering:

- A broader range of options for parents to balance working and caring

- A new model of parenting support

- New developments in child health, including a dedicated child health workforce

- Reform of the ELC (ELC) system, including a new funding model

- A package of measures to tackle early childhood poverty.

This strategy has many implications for the planning and design of ELC settings and how these settings interact with and influence the design of the public realm. For instance, the strategy promotes public places that are inclusive and designed with babies and young children in mind. These should be places for children to play and learn, and provide opportunities for parents and young children to meet.

In terms of the design of settings, the strategy states that investment should facilitate the participation of all children in ELC, promote settings that are informed by UD and that are inclusive and accessible to all children, families and practitioners.

2.3 Understanding the Whole Person and the Needs of Diverse Users

Inclusive education, as demonstrated by AIM, takes a holistic view of the learner and embraces human diversity. The UD approach supports inclusive education on many fronts. Both UD and inclusive ELC increasingly consider the user or learner in biological, psychological and social terms - or as a ‘bio-psycho-social’ entity (Engel, 1981, Smith, 2002). This helps ensure a holistic understanding and treatment of the person.

The UD approach emphasises an inclusive education approach that must consider the variety of users in a typical educational environment. Petronis and Robie (2011) discuss the need to integrate everyone into all aspects of the built environment and outline the challenges facing public educational institutions around making learning environments supportive of all regardless of their learning or physical abilities. They argue that all users must be considered – students, staff and visitors – and contend that UD seeks to provide an optimal

environment for all users.

This inclusive educational approach is promoted in the Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Charter and Guidelines for Early Childhood Care and Education (DCYA, 2016: 38/39). Referring to the physical environment the guidelines highlight the following:

- General layout and accessibility of the environment for children with a disability and the need for possible environmental adaptations (e.g. for sensory exploration).

- Accessibility of information for families and children, keeping in mind language and literacy issues, accessible formats such as audio or Braille, and availability of staff who can communicate through sign language.

- Storage and accessibility of materials for all children. Placing ‘the best’ books on the top shelf means that children do not get the opportunity to explore books independently.

These guidelines acknowledge the diversity of a typical ELC setting, and align

with the UD approach by arguing that these settings must:

- Ensure that service planning and provision embraces the needs of all children and works to deliver an inclusive and accessible environment for all.

- Enable all children to meaningfully participate in all aspects of the curriculum, and extend learning to challenge and promote the individual

child’s abilities and development. - Ensure that children of all abilities have equal access to culturally and developmentally appropriate play-based educational activities, both indoors and outdoors, which develop their understanding, dispositions, skills and holistic development.

In a similar manner, the Department for Children, Schools and Families (henceforth referred to as DfCSF) in the UK has prepared design guidance (DfCSF (UK), 2008) for mainstream and special schools. This guidance refers to a wide spectrum of ages including early years, and outlines four main special needs and disabilities that need to be considered in the educational setting.

These include:

- Cognition and learning: specific learning difficulty (SpLD); moderate learning difficulty; (MLD); severe learning difficulty (SLD); profound and multiple learning difficulty (PMLD)

- Behaviour, emotional and social development (BESD)

- Communication and interaction: Speech, language and communication needs (SLCN); autistic spectrum disorder (ASD)

- Sensory and/or physical: hearing impairment (HI); visual impairment (VI); multi-sensory impairment (MSI); physical disability (PD)

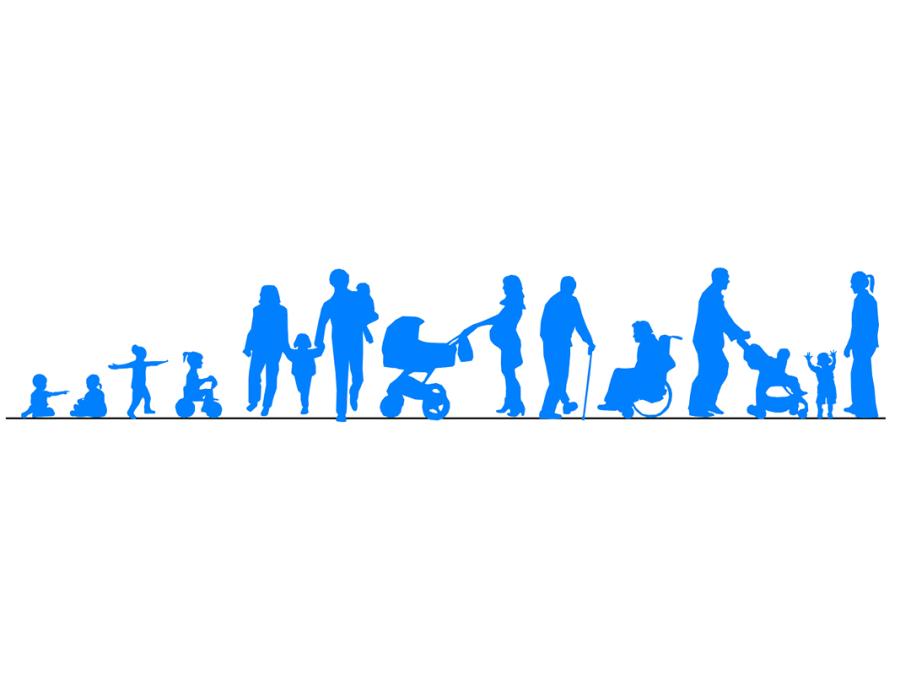

The above guidelines refer specifically to children with special needs and disabilities in both mainstream and special schools. The needs of these children, along with a wide range of ELC setting users need to be considered as part of the diverse and inclusive approach set out in the Irish early years policy discussed earlier. In fact, the full range of users is almost infinite, especially if the setting is integrated in the locality and provides some onsite services, such as a community space. The following sections identify a small range of specific users who may have particular needs in relation to the ELC built environment. It is hoped that identifying these users will help inform the UD approach presented in this report.

Figure 4. Various ELC setting users

2.3.1 All Children

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) describes its child-friendly schools (CFS) framework as promoting “child-seeking, child-centred, gender-sensitive, inclusive, community-involved, environmentally friendly, protective and healthy approaches to schooling and out-of-school education worldwide” (UNICEF, 2014).

Child-friendly environments must afford children space and time to play as this is an essential part of their physical, social and cognitive development (Gleeson and Creamer, 2012, Committee on Environmental Health, 2009). In the context of an ELC setting that accommodates a range of age groups it is important to provide age-appropriate social and recreation space within the setting. The Department for Education and Skills (henceforth referred to as DfES) in the UK has published guidelines around the design of school grounds and advises that provision must be made for differing children’s needs, whether this is age or ability related (DfES (UK), 2006). The adoption of certain spaces by different age groups is inevitable and it is suggested that sufficient, well designed space must be provided for different age groups to make age appropriate places, create conditions for greater positive social interaction, and reduce potential conflicts. Adopting a developmental perspective, the following overview of age-related changes, between birth and five years, is offered as a guide and acknowledges individual variation in development. It is important to stress that each child’s developmental trajectory is unique and that the role of the ELC practitioner is to support each individual child along his/her own emerging developmental path.

2.3.1a Infants (Birth to one year)

Babies develop from lying flat to acquiring great mobility. By the time they are one year old, many will have begun to sit up unsupported, crawl, observe the activities of others and show an interest in books, objects and games. Many children will be fully ambulant by around eleven months. Sleeping areas and nappy changing facilities are required.

Figure 5. Infant in Cheeky Cherubs, City Council Workplace Crèche, Cork City Hall, Cork

2.3.1b Toddlers (one to two years)

At this age children will begin to walk, initially with poor balance, to crawling up stairs, pushing, pulling, carrying and building. They spend much of their time on the floor, crawling, squatting, sitting, kneeling or mastering their walking skills. Their balance can be uncoordinated up to about eighteen months and they can tend to fall heavily. Many will have mastered self-feeding and be able to identify some simple familiar items. At eighteen months many children are capable of running. There can be much spillage and falling at this stage and they need a lot of supervision. Sleeping areas and nappy changing facilities are important features.

2.3.1c Children (two to three years)

Between the age of two and three-years, children have mastered many of the skills they have been developing. Usually, they run with confidence, climb, build large towers, and recognise details in pictures. Their language development is progressing well and their command of language can be quite advanced. To support the child and staff it is essential that the layout include a mixture of open space and smaller nooks to accommodate the activities in the setting. This is also the toilet training stage of development, so great consideration must be given to this important milestone. The location of and attitude to toilet training can have a profound effect on the child. It must be seen as a natural event, and children should have free access to the child-size toilets or potties and wash hand basins. Good hygiene facilities and practices are very important. Children benefit from spaces with a balance of hard and soft landscape (including grass, trees etc), and spaces that balance risk and challenge to allow children to safely challenge themselves.

Figure 6. Young child at play, Benbulben Creche, Sligo Town, Co. Sligo

Shelter and shade should be provided through planting, playhouses or more flexible covers such as canopies or sails. Transitional areas between internal and external space are beneficial, particularly if they are covered and extend the indoor space. Changes in topography and a variety of textures, colours and shapes are important but some space should remain free to allow children invent their own activities. Adaptability will help in this regard, and will allow staff to successfully use the space. While safety and appropriate access need to be considered, young children require supervision and therefore easy visual and physical access to these spaces for supervising adults is important. Sleeping areas or facilities will also be required.

2.3.1d Pre-school (three to five years)

At this age children will usually have developed competent locomotive skills and can jump, pedal and hop. They have greater control over their fine motor skills and can cut with a scissors and thread beads. Socially and emotionally they begin seeking more independence and are keen to please. During the preschool years children’s vocabulary and extensive comprehension continue to develop and they enjoy imaginative play.

Figure 7. Lux Childrens’ Club, Moate, County Westmeath

2.3.1e School-aged Children

While this review focuses on ELC settings and not primary schools, there are primary school design approaches and features that are relevant to ELC settings and these are reported on to inform the overall UD approach. School-age services can also be referred to as after-school or out-of-school care. Given the provision of school-age services can include children aged 4-14 years, special consideration needs to be given to designing a physical environment that supports the varying rates of development and growing needs of this older age group. Creating the right environment will support emerging independence, and in developing young people to their full potential. It will provide security and opportunities for relaxation, along with activities, interactions and ongoing development in an appropriately designed care environment. The positioning of the school-age service within a building is important. In certain circumstances an upper floor of the building will be considered suitable.

Primary school children need space that appeals to their intellect, sense of fun and need for physical and mental exploration. It is helpful to provide a number of seating options to facilitate various social and teaching arrangements and this should be reinforced through a management approach which allows children and staff to adapt to the space. Providing ‘open ended’ playground markings allow a diversity of uses and make sure there are opportunities for both formal (i.e. physical education, PE) and informal physical activities. Walsh (2006) points out that older children get hot and tired during play and recommends that water fountains and rest areas should be provided.

Outdoor areas should provide well-designed, comfortable social and eating spaces. Ideally some of these spaces should be covered and furnished with seating so as to provide high quality spaces that can also be used for teaching purposes. While it is important to provide larger spaces for traditional activities such as football, it is also worth considering other approaches such as activity trails which are large enough and provide sufficient challenge. The design of space must reflect the age of children; younger children may need the ‘safety’ of some level of containment, while older children coming into the setting as part of an after-school service may prefer an environment which is more adult-like.

Figure 8. Children of all abilities enjoying the outdoors, Graiguecullen Parish Childcare Centre, County Laois

In the context of a UD ELC setting, the design of space for the age groups identified above should include provision for children with special educational needs or disabilities. However, given the complexity of these needs they are examined separately in a number of sections that follow. A setting will benefit from shared spaces that tie these individual areas together and provide common space for social interaction and mixing of age-groups. The DfES guidance referred to earlier points out that the relationship between various age-

appropriate spaces is important in terms of integration and transition, and that a balance must be stuck between the safety of all children and the avoidance of duplication of resources (DfES (UK), 2006). The creation of a child-friendly environment is not only about creating a safe and secure setting but also about providing them with the space and time to develop physically, socially, emotionally and intellectually. The following key issues must be considered:

Key considerations for the design of a UD ELC setting

- Consider UNICEF’s child-friendly schools framework which promotes “child-seeking, child-centred, gender-sensitive, inclusive, community-involved, environmentally-friendly, protective and healthy approaches to schooling and out-of-school education...”

- Consider how the spatial and physical nature of the surrounding community supports the ELC setting, provides access, and creates safe opportunities for physical activity (including walking or cycling to school), play and contact with nature.

- Use the UD ELC setting to create child-friendly environments to afford children space and time to play as an essential part of their physical, social and cognitive development.

- Provide age-appropriate spaces that respond to the needs of various age groups ensuring these spaces are safe while affording appropriate levels of challenge to support development.

- Ensure there are shared spaces to provide appropriate integration and transition between all age groups.

2.3.2 People with Cognitive, Learning, Behavioural, Communication and Interaction Difficulties

Referring back to the DCSF design guidance (2008), three of the four categories relate to non-physical disabilities and include:

- Cognition and learning,

- Behaviour,

- Emotional and social development,

- Communication and interaction.

The guidance details a number of design issues associated with each of the specific needs and are outlined below.

According to this design guidance, children with cognitive and learning difficulties may need practical sensory and physical experiences to support learning in relation to abstract ideas and concepts. These needs must be considered as part of school design and attention must be paid to good acoustics for speech and language support and storage for learning aids and other teaching resources. Good visibility to help with supervision and well-designed wayfinding to aid independence are also important issues.

To ensure the inclusion of children with behavioural, emotional and social development difficulties, disruptive, disturbing or hyperactive behaviour, or a tendency to be withdrawn or isolated the design issues relate to good sightlines which create a balance between privacy and supervision, secure storage and tamper proof services, low health and safety risks, and large spaces for social and outdoor activities.

For children with communication and interaction difficulties the design of a setting should provide a legible layout with clear signage that is easily comprehended while providing good lighting and acoustics. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) may be required to provide additional sound or speech supports. Children with Autism Spectrum Differences (ASD) are often considered in this category and will benefit from the measures described above; however they may also require additional measures to ensure an inclusive education approach (Ring, Daly and Wall, 2018). The DCSF design guidance recommends a simple layout containing the following: “calm, ordered, low stimulus spaces, no confusing large spaces; indirect lighting, no glare, subdued colours; good acoustics, avoiding sudden/background noise”. Safe indoor and outdoor spaces for withdrawing and calming down are recommended along with precautions around health and safety and tamper proof services.

These ASD-specific design issues align with those highlighted elsewhere in literature which discuss an ASD-friendly design approach (McAllister and Maguire, 2012, Mostafa, 2008, Notbohm, 2005, Scott, 2009b). A recent publication ‘Aldo goes to Primary School: Experiencing School through the Lens of the Autistic Spectrum’, examines the experience of primary school from the perspective of a young boy with ASD. McNally et al (2013), illustrate the challenges faced by a person with ASD when attending school. The authors describe how people with autism may have difficulty comprehending verbal and non-verbal communication. They may be hypersensitive or hyposensitive (under-sensitive) to sensory information such as: sight, sound, touch, taste, smell, balance, or proprioception - relating to stimuli that are produced and perceived within an organism, especially those connected with the position and movement of the body (Oxford Dictionaries, 2014). These challenges can be experienced even more strongly by very young children (Ring, Daly and Wall 2018).

In terms of the spatial and physical design of the school environment, McNally et al (2013) argue that the following key issues are critical to providing an appropriate environment for children with ASD:

- Arrival: the noise and activity of a setting in the morning can be problematic so the transition from home should be as straightforward and stress free as possible. Ensuring parents can accompany a child as far as possible or providing a secondary entrance with less activity may help this transition.

- Wayfinding: circulation to and around the setting must be clear and comprehensible.

- Legibility: visual cues to help with orientation and identify the purpose of individual areas coupled with personalised spaces using colours or recognisable objects, and dedicated spaces for particular activities will help with overall legibility.

- Scale and organisation: smaller settings or those that are broken down into smaller ‘neighbourhoods’ will provide a more navigable and legible environment that allows easier orientation and is less daunting or disorientating.

- Threshold: any transition or change in environmental conditions can be problematic and so any space that allows a child to prepare and reorient themselves will be helpful.

- Classroom: a well-ordered and structured space which has identifiable areas for specific tasks or activities will help provide a secure and familiar space for a child with ASD.

- Sensory issues: certain environmental triggers can often upset or distract a child with ASD. It is important to:

avoid bright shiny surfaces, bold geometric patterns or strong textures as these can cause visual distraction.

reduce excessive sunlight and glare.

be careful with fluorescent lighting as the flicker form this lighting may be perceived by those who are hypersensitive.

use good acoustic design to mitigate excessive noise and avoid strong smells which can be problematic for people with ASD. - Engaging with others: provide respite spaces in circulation areas, playgrounds or other social spaces from which the child can retreat but still maintain a view to activities to avoid being totally removed or isolated. The provision of secure dedicated play space for a particular class or age group may be helpful.

- Quiet space: greater retreat than outlined above may be beneficial and the provision of a quiet, calm and restful space which is acoustically separated from the activity area will help.

- Safety and security: children with ASD may attempt to ‘escape’ so security and supervision is important, especially when outside. They may often have a diminished sense of fear which can lead them to venture beyond safe boundaries and thus increase risk, particularly when sensory or co-ordination difficulties are also a factor.

The above issues are also major challenges in terms of ELC setting location, approach and adjacent spaces in the community. Hypersensitivity can cause many obvious problems for people in public spaces or streets where noise, crowds and bright lights are part of everyday life. Traffic lights, pedestrian stop lights, the sound of oncoming traffic, emergency sirens or public announcements may be stressful and disorientating. On the other hand, people who are hyposensitive or, for instance, those who experience hypo-tactility (children who are hypo-tactile do not appear to feel pain or temperature) may fail to notice or understand tactile paving.

As discussed previously, the open and publicly accessible nature of an ELC setting will result in a wide spectrum of users. In some cases, for example family resource centres, this may include older people availing of further education or using the setting as part of the community. Grandparents often collect their grandchildren. So while the setting is primarily designed for young children, the users can cover a wide age spectrum. Issues around dementia may become a design factor to ensure that all people can use the setting equally.

Dementia friendly environments seek to support people with cognitive decline and other age-related difficulties. Fortunately, many of the ASD-friendly design issues explored above align with dementia-friendly requirements and this should be used to a designer’s advantage when creating educational settings. Dementia-friendly environments have been described by Marshall (1998) who recommends that a dementia-friendly approach should include: distinct spaces for different functions; safe outdoor space; the use of personalisation; good signage with multiple cues such as sight, smell and sound; objects used for orientation; enhanced visual access; and, control of stimuli, especially noise. Burton and Mitchell (2006), propose a six key design principles to support dementia friendly streets which include: familiarity; legibility; distinctiveness; accessibility; comfort; and, safety.

Children with cognitive, learning, behavioural, communication and interaction, or other related difficulties present a huge variety of needs that vary greatly from person to person. However, heightened sensitivity to sensory information often plays a significant role in how they perceive and operate in an environment, which in turn greatly influences their comfort, wellbeing and ability to undertake tasks and participate in everyday activities. Taking into account the heterogeneous nature of people with cognitive, learning, behavioural, or communication and interaction difficulties, and acknowledging the diversity of their needs, the following key design issues should be considered in any UD educational environment:

Key considerations for the design of a UD ELC setting

- Create more human-scale environments by avoiding very large buildings or by breaking down larger settings into smaller parts that provide a more manageable, navigable and legible environment.

- Ensure that the layout is clear and comprehensible and the environment provides multiple sensory cues and good signage to help with legibility and wayfinding.

- Provide good sightlines to support this legibility and to allow child supervision.

- Consider alternative arrival routes for people who may be hypersensitive and have trouble dealing with typical activity associated with the start of the day.

- Carefully consider threshold spaces which introduce environmental change. Consider transition spaces that allow a person to prepare

and reorient themselves. - Provide respite spaces in circulation areas, playgrounds or other social spaces from which the child can retreat but still maintain a view to activities to avoid being totally removed or isolated.

- For a greater level of retreat provide quiet withdrawal spaces which are acoustically separated from the main activity.

- Provide calm, well ordered and structured external and internal spaces with identifiable areas for specific tasks or activities to help

provide a secure and familiar space. - Provide extra space for practical sensory and physical experiences to support learning in relation to abstract ideas and concepts. Provide

space for additional learning aids. - Pay attention to all sensory stimuli avoiding excessive noise, very strong odours, or visual stimuli such as glare, bright shiny surfaces,

bold geometric patterns or strong textures. - Carefully consider safety and security and provide tamper proof services, secure storage, and minimum health and safety risks.

2.4 People with Visual Difficulties

People with visual difficulties have a variety of different wayfinding techniques depending on the navigational aids they use and these are outlined by Atkin (2010). People with residual sight tend to rely on the limited sight they have, as well as sound and memory of the space they are using. For these users, tonal contrast between the pavement and carriageway is important; meaningless colour changes can be confusing and sudden level changes without indication via colour changes can cause trip hazards.

Figure 9. A person with visual difficulties may use a cane or a guide dog

Long cane users rely heavily on tactile walking surface indicators, audible information from directional traffic movement, and audio pedestrian lights. They tend to use the building line as an orientational cue but will avoid the kerb line as they feel unsafe walking close to traffic. Wide open spaces without good navigational cues can cause disorientation. Level surfaces with no height differences between the path and carriageway can pose difficulties for long cane users as there is no way to detect movement from the path onto the road (Atkin, 2010).

In relation to navigational methods used by guide dog users, Atkin (2010) found they rely on a combination of on tactile paving, signals received from the dog and audible information such as traffic noises. Guide dogs are trained to orientate themselves using the kerb line and the building line. Guide dog users can use tactile paving to differentiate between the path and carriageway; however, if the tactile paving is missing for whatever reason, and the surfaces are level, a person with visual difficulties has no way of correcting the dog’s mistake, and may be placed in a dangerous situation.

The DCSF design guidance (2008) outlines a range of design issues in relation to children with visual difficulties. These include:

- Good quality ambient and task lighting and controls,

- Visual contrast, cues, symbols, tactile trails and maps,

- Good acoustics, low background noise, speech and audio aids,

- Sounder alarms, health and safety warnings,

- VI (visual impairment) resource room,

- Storage and maintenance of technical aids.

The DCSF (2008) document refers to the need for mobility training (i.e. training that allows an individual to move safely and independently through the environment). This typically requires a dedicated mobility training room within the school. However, it is noted that mobility training can take place around the school and in external spaces on the school grounds that contain obstacles or various surfaces to negotiate. This will help the child to develop independence by providing safe simulations of many of the hazards a student may encounter outside the school.

While the design requirements in relation to people with visual difficulties will depend on the location and context of the setting, and the specific needs of the students, staff or members of the community, at a minimum the following key issues should be considered:

Key considerations for the design of a UD ELC setting

- Provide convenient, clearly defined legible travel routes with carefully located, well-designed signage for enhanced wayfinding.

- Provide circulation routes that support navigation through multiple sensory cues including visual (e.g. colour and tonal contrast or landmarks), smells (e.g. fragrant planting), or distinct sounds (e.g. chimes or moving water).

- Provide conveniently located private and sheltered vehicle or public transport drop-off points.

- Ensure good levels of natural and artificial lighting with even illumination especially along circulation routes.

- Use tactile paving surfaces to indicate hazards, level changes or steps and generally aid navigation.

- Ensure circulation routes are sufficiently wide to cater for a person using a long cane, somebody with a guide dog, or a teacher or parent walking beside a child with visual difficulties.

- Consider how the school and ELC setting can be used for mobility training using various kinds of mobility aids or a guide dog.

- Consider what ICT solutions may be beneficial to people with visual difficulties in terms of wayfinding and how these might be included or influence the design of the setting.

2.4.1 People with Mobility Difficulties Including Wheelchair Users

Research shows that people with mobility difficulties are supported by environments that are free of clutter, contain even surfaces and have limited crossfall, which is a feature of pavement surfaces designed to support drainage, (Department for Transport UK, 2011b). Those with limited mobility, arthritis sufferers, and cane or rollator users, need plenty of well-placed seating to afford resting points. The United Kingdom based Manual for Streets (Department for Transport UK, 2007) suggests seating should be provided at 100 metre intervals along key pedestrian routes and be located where there is good natural surveillance. The UK Inclusive Mobility (Department for Transport UK, 2005) guidance refers to recommended walking distances for people with various mobility difficulties and points out that while a typical wheelchair user may need to rest approximately every 150m, a person with mobility difficulties and who uses a stick would need to rest every 50m.

Regarding mobility issues specific to the educational setting, the DCSF design guidance (2008) recommends the following: higher accessibility standards; greater space for carers and bulky mobility equipment and greater storage area; shallow pitch stairs; rest places; greater health and safety awareness along with provisions for assisted emergency escape.

Figure 10. A child using a rollator on an outdoor path, Graiguecullen Parish Childcare Centre, Graiguecullen, County Laois

In terms of the overall ELC setting circulation it is important to provide short, conveniently located, level, clutter-free circulation routes that are accessible and usable by those with mobility difficulties. For many people with mobility difficulties vehicles provide an important form of transportation, therefore the setting must ensure these users can access and circulate to key points within the site such as building entrances. Conveniently located parking spaces, set down areas or dropping-off spaces with shelter must be provided for those with a restricted travel range such as people with mobility or sensory difficulties (DfCSF (UK), 2008).

People with mobility difficulties will have specific requirements for outdoor space including: play areas with sufficient space for specialised play equipment; outdoor PE facilities such as all-weather pitches for ease of movement (drainage can be an issue in all-weather pitches); covered outdoor space providing a transition between indoor and outdoor spaces; garden areas with raised beds for wheelchair users or those with restricted mobility. While the integration of children with mobility difficulties is essential, it may be beneficial to provide some dedicated spaces to protect vulnerable children from the boisterous play that occurs naturally. Dedicated trails or routes can provide protection while supporting mobility training where safe simulations of everyday hazards can be introduced as part of the learning process.

Key considerations for the design of a UD ELC setting

- Provide vehicle access, circulation, parking or set-down and drop-off areas to suit people with a limited travel range.

- Provide short, level, slip resistant, and clutter free circulation routes in convenient locations.

- Ensure circulation routes are sufficiently wide to cater for a person using mobility equipment or being assisted by another individual.

- Provide seating, respite areas, and sheltered seating or social areas in key external spaces and along circulation routes.

- Provide adequate external space and storage for bulky mobility equipment.

- Consider how the school and ELC setting can be used for mobility training where everyday hazards can be introduced in a safe environment.

- Provide protected play or circulation areas for more vulnerable children while also considering integration and transition from protected spaces to shared spaces.

2.4.2 People with Hearing Difficulties

In terms of the external environment, people with hearing difficulties may have associated balance issues and therefore surfaces with appropriate crossfall will provide greater ease and comfort when walking (Department for Transport UK, 2011a). During field studies for research undertaken by Grey et al. (Grey et al., 2012) participants with hearing difficulties, who also represented the Irish Deaf Society, spoke about the need for wider footpaths to allow two people to walk comfortably side-by-side to facilitate lip-reading or communication through sign language. The issue regarding the inability to hear oncoming traffic or emergency vehicles which were out of direct view or approaching from behind also arose. This was highlighted as an issue for individuals needing to cross a street in moving traffic or navigate through a space where there is a certain mix of motorists and pedestrians. These issues need to be carefully considered with regard to approaching, entering and circulating within ELC settings.

Referring to educational design issues specific to those with hearing difficulties, the DfCSF design guidance (2008) focuses on how to minimise distraction and support diminished hearing by providing high quality acoustics and reducing background noise. To support text or lip-reading they recommend using subdued colours, high quality low glare lighting, and the avoidance of shadows causing silhouetting. In terms of technology the guidance proposes “visual alarms, sound-field systems, hearing loops; storage & maintenance of technical aids” (p.199).

Key considerations for the design of a UD ELC setting

- Ensure circulation routes are wide enough to allow at least two people to walk comfortably side-by-side to facilitate lip reading or communication through sign language.

- Ensure acoustic conditions are optimised for people with hearing difficulties especially in noisy environments such as playgrounds or areas with potential traffic hazards.

- Consider what ICT solutions may be beneficial for people with hearing difficulties and how these might be included or influence the design of the ELC setting.

2.4.3 An Older Person

Considering the family-centred ethos of the Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Charter and Guidelines for Early Childhood Care and Education (DCYA, 2016), it is important to acknowledge the key role grandparents and older relatives can play in the care of children attending an ELC setting. Sometimes they will be the person dropping off and picking up the child, and therefore their needs, in terms of accessing and using the setting must be taken into account. In general, the quality of the built environment has been shown to contribute to older people’s health through opportunities to be active and through the provision of spaces where people can socialise (Sugiyama and Ward Thompson, 2007). However many of these activities require a certain level of physical strength and fitness and often the built environment presents barriers that older people find difficult to negotiate (Sugiyama and Ward Thompson, 2005) due to age related biological changes such as mobility, visual or hearing difficulties.

Figure 11. Grandparents are important stakeholders in a ELC setting

Research carried out by the Inclusive Design for Getting Outdoors (I’DGO) research consortium examined the many issues that affect older people in the built environment and they have published a set of findings and guidelines (I’DGO, 2010). This research involved focus groups, interviews and onsite audits and found a number of common preferences and concerns for older people. Most of the respondents preferred wide, uncluttered footpaths with minimum temporary obstacles and for the parking of cars on footpaths to be discouraged. The research also found the respondents favoured traditional kerbs, and where required, dropped kerbs to clearly differentiate the carriageway from the footpath. However, many found the presence of tactile paving at the dropped kerb uncomfortable and some reported that they felt they could twist their ankle. Tactile Work Surface Indicators (TWSIs) such as tactile paving can, however, provide valuable mobility assistance and enhanced accessibility. In relation to pedestrian crossings, most felt a signal-controlled crossing suited them best, while the least favoured was informal or uncontrolled crossings. Most of the older people interviewed welcomed the presence of seating as rest points at appropriate distances but would also use informal objects such as low walls or seating in bus shelters to rest.

As dementia is more prevalent among older people, the design of a dementia friendly environment will obviously be beneficial for many older people. A range of dementia friendly design issues have been discussed earlier and it was pointed out how these measures are in many ways closely aligned with an autism-friendly approach. In fact many of these measures, such as enhanced legibility, or the use of multiple sensory cues for orientation and wayfinding, are also beneficial for other users such as those with visual or hearing difficulties.

An ELC setting will need to provide a supportive environment for older people in terms of age-related mobility, visual and hearing difficulties, or cognitive difficulties caused by dementia. It is equally important to provide an environment that supports positive intergenerational interaction. At a minimum the design of a UD ELC setting that successfully caters to older people in an intergenerational context should consider the following:

Key considerations for the design of a UD ELC setting

- Provide vehicle access, circulation, parking or set-down and drop-off areas to suit older people with a limited travel range.

- Provide short, level, slip-resistant, and clutter free circulation routes in convenient locations.

- Provide convenient, clearly defined and legible travel routes supplied with carefully located and well-designed signage for enhanced wayfinding.

- Provide circulation routes that support navigation through multiple sensory cues including visual (e.g. colour and tonal contrast or landmarks), smells (e.g. fragrant planting), or distinct sounds (e.g. chimes or moving water).

- Ensure good acoustic conditions particularly in areas adjacent to noisy activities such as playgrounds or main circulation routes.

- Consider what ICT solutions may be beneficial for people with visual or hearing difficulties and how these might be included or influence the design of the ELC setting.

Strange et al (2001) propose that educational environments greatly influence educational outcomes and argue “that educational settings designed with an understanding of the dynamics and impact of human environments in mind will go further in achieving these ends.” UD engages with these dynamics and impacts and has the potential to create the supportive educational environments as discussed by Dewey and Strange. To understand the role of UD in creating inclusive ELC settings, it is important to examine the various design goals, principles, guidelines and processes which are encompassed by UD. The following sections examine these and this chapter concludes with a brief discussion about the role UD has in supporting inclusive ELC settings in Ireland.

2.5 Universal Design Goals and Principles

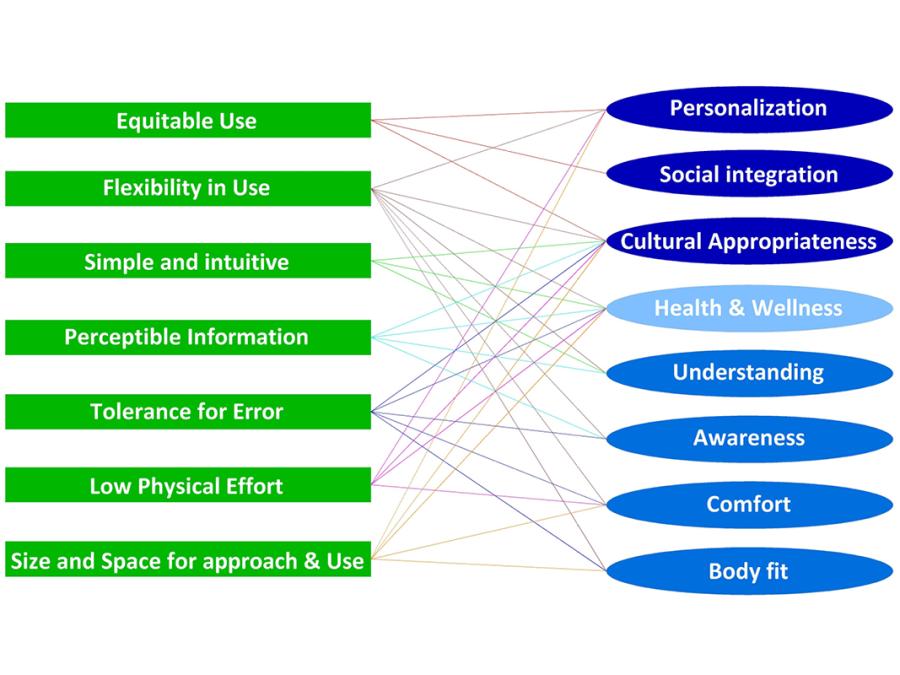

Steinfeld and Maisel (2012) outline a set of UD goals that relate to human performance, health/wellness and social participation and are composed of the following:

- Body fit - accommodating a wide a range of body sizes and abilities.

- Comfort - keeping demands within desirable limits of strength and stamina.

- Awareness – ensuring that critical information for use is easily perceived.

- Understanding – making methods of operation and use intuitive, clear and unambiguous.

- Wellness – contributing to health promotion, avoidance of disease and prevention of injury.

- Social integration – treating all groups with dignity and respect.

- Personalisation – incorporating opportunities for choice and the expression of individual preferences.

- Cultural appropriateness – respecting and reinforcing positive cultural values and local context.

Steinfeld and Maisel developed the above goals to add clarity of purpose to the internationally established UD principles (Kose et al., 2001, Preiser and Smith, 2011) which are as follows:

- Equitable use – the design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

- Flexibility in use – the design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

- Simple and intuitive – the design is easy to understand regardless of the user’s knowledge, language skills or current concentration levels.

- Perceptible Information – the design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions of the user’s sensory abilities.

- Tolerance for error - the design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

- Low physical effort – the design can be used efficiently and comfortably with minimum fatigue.

- Size and space for approach and use - design provides appropriate size and space for reach and manipulation, regardless of user’s body size posture or mobility.

Figure 12. Relationship between Universal Design Principles and Universal Design Guidelines (adapted from Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012)

Lissner looks at the seven UD principles in relation to educational settings and for each principle he offers a description and an exemplar. The intention is to provide an outline of how typical design issues experienced in an educational setting could be resolved within the framework of the seven UD principles (Lissner, 2007).

Table 1. The Seven Principles of Universal Design for the Built and Learning Environments (Lissner 2007)

Equitable use: welcoming to diverse groups; provides for equivalent if not identical participation and effort. Consider characteristics such as height, weight, strength, vision, hearing, gender and cultural/background, experiences of all potential users.

Exemplars: entrances at grade, captioned media, accessible web design for voice output.

Flexibility in use: adaptability of the overall spaces over time (sustainability) as well as flexibility and control by the users in interacting with specific elements and functions.

Exemplars: typical gendered group restrooms vs. individual/family restrooms, alternative methods of demonstrating learning, cascading style sheets in web design.

Simple and intuitive use: welcoming to non-native English speakers and individuals from diverse backgrounds; provides consistent forms, locations, and cues for way finding, operation, or interaction.

Exemplars: building or directional signage that includes local area maps or floor plans, course management system instructions that consider the range of experience with the technology by participating students and faculty.

Perceptible Information: communicate information effectively across the spectrum of ambient conditions (light, sound, activity) using a variety of modalities (tactile, visual, auditory, linguistic).

Exemplars: light strobe and auditory output on alarms, pictograms on signage, volume, spacing, and size of text on PowerPoint slides.

Tolerance for error: minimise hazards and the adverse consequences of unintended actions, variations in pace, or vigilance; provide warnings or fail safe features.

Exemplars: changes in texture and colour at elevation changes, the “undo” option in computer software, opportunities for feedback prior to grading.

Low physical effort: efficient building systems; minimize user fatigue by reducing the need for sustained physical effort, allowing for neutral or

ergonomic body positioning and reasonable operating forces.

Exemplars: sustainable and green building technologies, walking distances from transportation points, maintaining low slopes on ramps and paths of travel, articulating keyboard trays in computer labs, seating options in classrooms.

Size and space for approach and use: appropriate space for approach and reach across user heights, sizes, and relative position; appropriately sized elements to allow manipulation across a range of hand sizes and reach ranges.

Exemplars: mounting heights that are comfortable for children, adults, or wheelchair riders, adequate space at computer workstations (aisles, table surface, and knee clearance), adequate space to respond to test questions.

2.6 Conclusion

This chapter sought to outline the key components of a UD approach and how this relates to the design of the ELC setting. As stated previously, UD is not only about removing barriers, but about creating positive environments to maximise inclusion and the empowerment of all people. If an ELC setting is to be an inclusive environment it must be accessible, easily understood, and usable to the greatest extent by all users regardless of age, size, ability and disability.

Key issues arising from Chapter 2

| UD supporting inclusive education |

| Through its holistic and integrated human-centred design approach for all people regardless of age, size, ability or disability, UD supports the goals of inclusive education, which take a holistic view of the learner, promotes participation and embraces diversity. |

| The emphasis on activity and participation in UD, expressed through the ‘Person-Activity-Environment’ (PAE) interaction, helps to highlight how human activities, participation and performance are either restricted or enhanced by the environment. This PAE interaction is therefore crucial in an inclusive education setting. |

| UD supporting inclusive education |

| The UD ELC setting must cater to a diverse range of children, staff and community needs and preferences. Children across early years, primary, post primary and further education will present a wide variety of age and ability related needs. Older people, or members of the local community, will also have specific needs based age related biological changes such as mobility difficulties, visual or hearing difficulties, or cognitive difficulties such as dementia. |

| As part of the above, the varying and specific design requirements associated with special educational needs and disabilities must include: children with cognitive and learning difficulties; children with behaviour, emotional and social development difficulties; children with communication and interaction difficulties (including those on the Autistic Spectrum); and those with visual, mobility, or hearing difficulties. |

| This chapter has examined a range of design approaches and features that cater to the multiple needs of users outlined above. The UD approach must be used to balance the design response in order facilitate all users equally and create an inclusive ELC setting environment for all. |