Key pedagogical issues for early learning and care settings

3 Key Pedagogical and Care Issues for Early Years Settings

Figure 13. Asilo Nido La Chiocciola, San Miniato, Italy

This part of the review focused on reviewing literature relevant to Early Learning and Care (ELC), to include key pedagogical and care issues. The findings of this literature review were used to provide an evidence base which underpins the Universal Design Guidelines for Early Learning and Care settings. Both peer-reviewed and grey literature were examined in order to identify national and international best practice regarding Universal Design (UD) and the built environment in ELC settings.

The core quality standards for ELC settings outlined in Síolta, the National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education (CECDE, 2006), provided an appropriate structure and context to guide this literature review. The literature review acknowledges that the Síolta Principles and Standards of Quality are closely aligned with those of Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework (NCCA, 2009,) as articulated in the Curriculum Foundations section of the Aistear Síolta Practice Guide (NCCA, 2015). The Literature Review is presented with reference to:

• Rationale

• Literature review methodology

• The Rights of the Child

• The Child and Parents and Families

• The Child and Interactions

• The Child and Play

• The Child and Professional Practice

• The Child and Community Involvement

• Limitations and Conclusion

3.1 Rationale

The Síolta principles of quality embody the vision, which informs and provides a context for quality practice in early childhood education and care (ECEC) in Ireland (CECDE, 2006). Síolta, in the first of its twelve principles affirming the value of Early Childhood, states that “early childhood is a significant and distinct time in life that must be nurtured, respected, valued and supported in its own right” (CECDE 2006:6). Other key principles include Children First; Parents; Relationships; Equality; Diversity; Environments; Child Welfare; the Role of the Adult; Teamwork; Pedagogy and Play. The principles of quality underpin the standards and components of quality, which further elaborate on, and define quality practice. The breadth of the sixteen Síolta standards is very wide, incorporating the Rights of the Child; Environments; Parents and Families; Consultation; Interactions; Play; Curriculum; Planning and Evaluation; Health and Welfare; Organisation; Professional Practice; Communication; Transitions; Identity and Belonging; Legislation and Regulation and Community Involvement (CECDE, 2006).

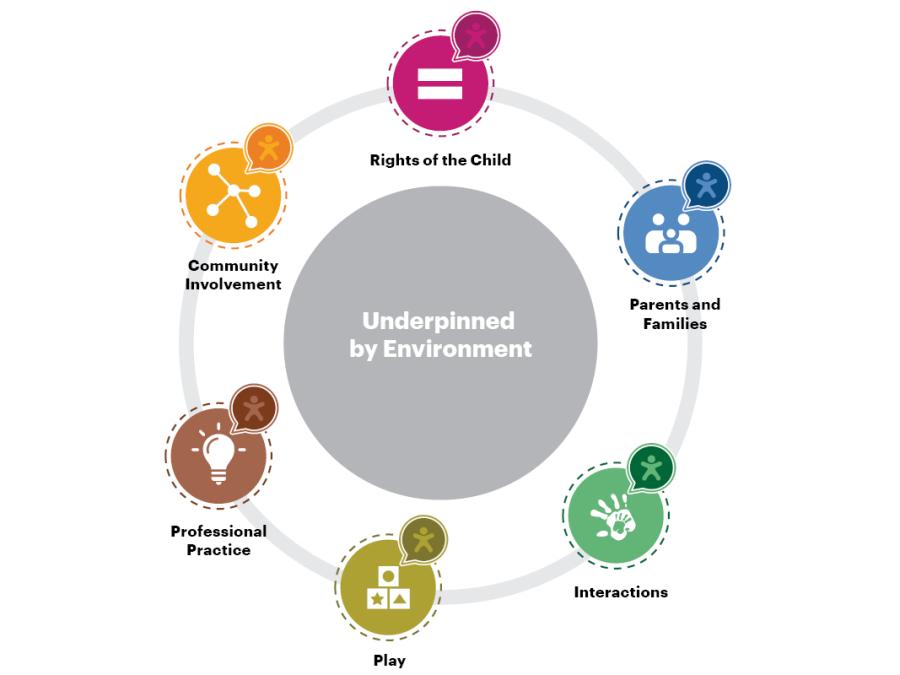

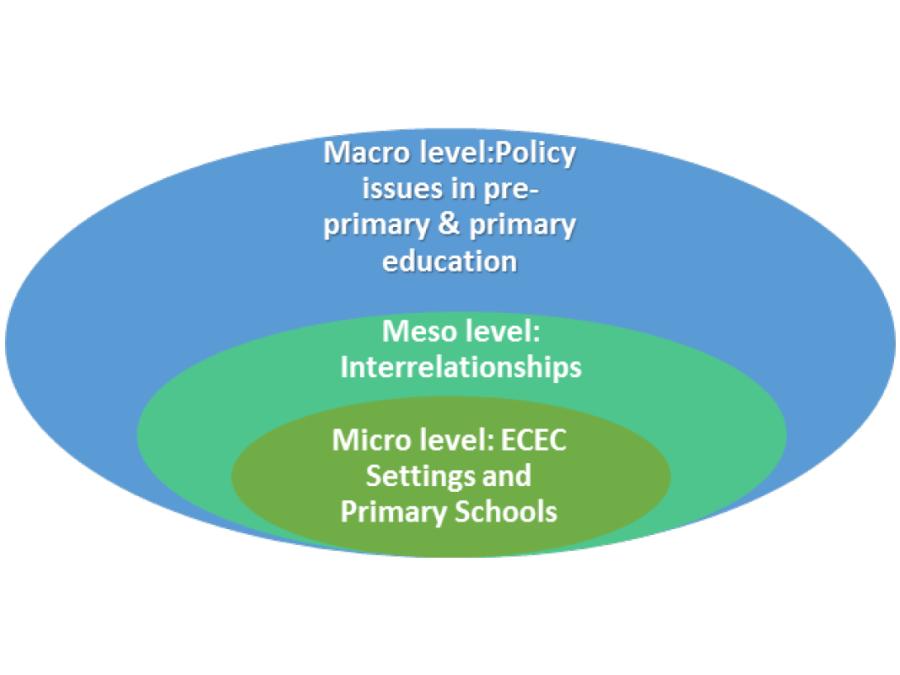

Following extensive discussion with both the partners and Steering Committee, for the purposes of the development of the Universal Design Guidelines for Early Learning and Care settings, we focused on six of the sixteen standards, which the combined experience and expertise of the group consider have particular resonance for UD in the context of ELC settings. These are Standard One: The Rights of the Child; Standard Three: Parents and Families; Standard Five: Interactions; Standard Six: Play; Standard Eleven: Professional Practice and Standard Sixteen: Community Involvement (CECDE, 2006). Given that the Universal Design Guidelines relate completely to ELC environments, clearly Standard Two: Environments is inextricably linked also. These principles are summarised at Figure 14.

Figure 14. Síolta Standards Guiding the Literature Review

The standards of quality in Figure 6 are further reflected in the Proposal for Key Principles of a Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care (Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission, 2014). The framework identifies three transversal issues, which it considers are fundamental to the development and maintenance of high quality ELC:

- A clear image and voice of the child and childhood should be valued

- Parents are the most important partners and their partnership is essential

- A shared understanding of quality

Together with these three transversal issues the principles promoting participation, strengthening social inclusion, embracing diversity, providing supportive working conditions including professional leadership and providing a curriculum focused on enabling children’s holistic development further resonate with the Síolta standards guiding the literature review (CECDE, 2006). Aistear: the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework similarly articulates twelve principles, presented in three groups (NCCA, 2009). These twelve principles intersect with Síolta and the European Framework in the areas of environments, play, equality and diversity and parents, family and community (CECDE, 2006; Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission, 2014).

3.2 Literature Review Methodology

A rigorous systematic approach to reviewing the literature was adopted in order to ensure it provided a synthesis of empirically-based literature and situated the project in a rich and embedded contextual framework to inform the project outcome (Bond et al. 2013; Gough 2007). An iterative approach to reviewing the literature was adopted, which continued to invigorate the process for the

duration of the project.

A two-strand approach was implemented, which included an empirical strand and an expert strand. The empirical strand comprised a systematic search of electronic databases and web searches related to peer-reviewed studies and the expert strand focused on accessing articles, reports, reviews and guidance based on expert opinion/professional experience related to ELC.

The literature review focused on identifying peer-reviewed publications published in English between 2008 and 2018, which were primary studies or reports of practice in early childhood education, relevant to the six Síolta (CECDE, 2006) standards guiding the literature review (See Figure 14. above). A computer-based search, included searches of the following electronic databases: PsycINFO; Science Direct; Scopus; ERIC and ProQuest. In addition web searches were undertaken using Google Scholar, Education-line and OECD Education at a Glance. Where during searches, literature pre-2008 emerged and was deemed to be significant in the context of the project, this literature was reviewed.

3.2.2 Expert Strand

The literature review focused on identifying and accessing articles, reports, reviews and guidance based on expert opinion/professional experience published in English between 2008 and 2018, which were relevant to the six Síolta standards guiding the literature review (See Figure 13 above) (CECDE 2006). Web searches were undertaken using Google, Google Scholar, Education-line and OECD Education at a Glance. As with the empirical strand, where literature pre-2008 emerged during searches and was deemed to be significant in the context of the project, this literature was reviewed.

3.2.3 Literature Searching

Prior to commencing the literature search, search terms were developed to locate the documents relevant to both the empirical and expert strand. In relation to early learning and care, both in Ireland and internationally, a range of terminology is used interchangeably. Applying Boolean Operators [AND/OR/ NOT], all of the search terms in Table 3. were used to locate the literature.

Table 2. Search terms for the literature review

| Early years settings |

| Early childhood settings |

| Early childhood care and education settings |

| Early childhood education and care settings |

| Pre-school settings |

| Pre-primary provision |

| Crèche |

| Childcare settings |

The exclusion criteria identified in Table 3 were applied to both the empirical and the expert Strands, with reference to the scope, study-type and time and place.

Table 3. Exclusion Criteria

| Scope | EC1 | Not focused on early childhood education |

| EC2 | Not related to the selected Síolta standards | |

| Study Type | EC3 | Literature in empirical strand not empirically grounded |

| Time and Place | EC5 | Literature from empirical strand and expert strand not within the specified time-frame (2008-2018) |

| Not written in English |

3.3 Synthesis of the Literature

The data extracted was initially organised as findings into categories, secondly the findings were analysed within each of these categories, and finally the findings were synthesised across the literature reviewed. The literature reviewed specifically focused on Síolta Standard One: The Rights of the Child; Standard Three: Parents and Families; Standard Five: Interactions; Standard Six: Play; Standard Eleven: Professional Practice and Standard Sixteen: Community Involvement (CECDE 2006).

3.3.1 Standard One: The Rights of the Child

Ensuring that each child’s rights are met requires that she/he is enabled to exercise choice and to use initiative as an active participant and partner in his/her own development and learning.

3.3.1a Children’s Rights and Our Responsibilities

Children’s rights are recognised in both national and international law, underpin government policy frameworks, are increasingly acknowledged in research and promoted in the context of initial early childhood teacher education (Ireland 2012; United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, (UNCRC) 1989; Department of Children and Youth Affairs (DCYA) 2014: Daly and Ring et al. 2016; Ring and Mhic Mhathúna et al. 2016; Ring, O’Sullivan and Wall 2018).

The UNCRC was ratified by Ireland in 1992. However, while the rights of the child are articulated as key principles in policy and practice contexts globally, ensuring these rights are vindicated continues to present as a contested space (Ring and O’Sullivan, 2016). Specifically the rights of children with additional needs have long been neglected in both national and international human rights law (O ’Mahoney 2006; Sabatello 2013). While the UNCRC explicitly included children with additional needs within its scope, discrimination and exclusion from participation in education, social and cultural contexts has continued to remain a feature of children’s and families’ experiences (Sabatello 2013).

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (UNCRPD), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2006 and ratified by Ireland in March 2018, represents a further step in mitigating this neglect. However, the degree to which international conventions are incorporated into domestic law is recognised as central to the implementation of international conventions and the associated vindication of the rights and freedoms associated with their scope (Lundy et al. 2013). While international policies and monitoring contribute to the realisation of children’s rights, the degree to which these rights are mirrored in national policies and provision remains the key determinant of whether these rights become a reality for children.

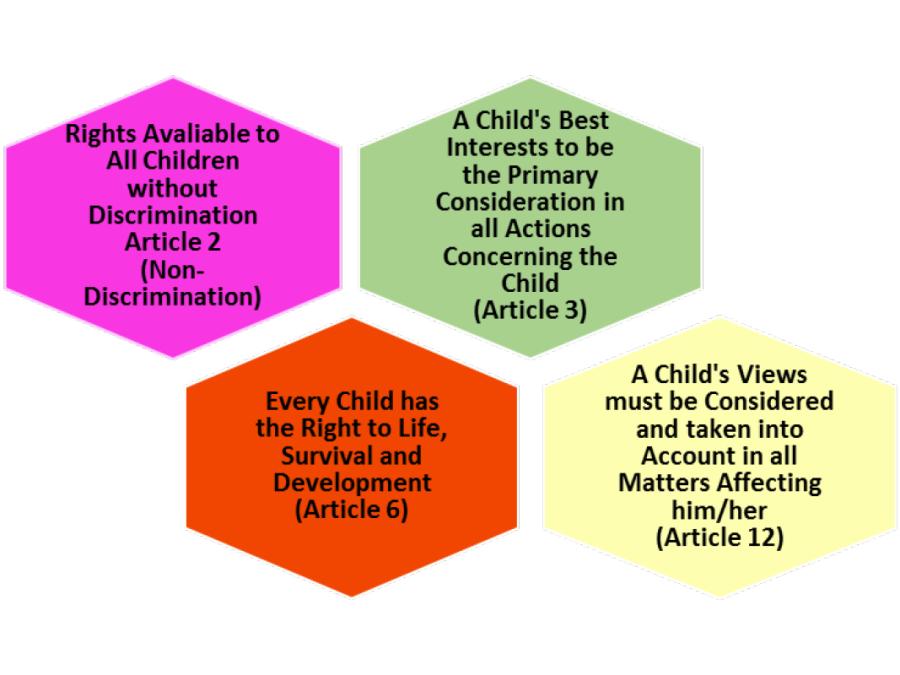

The inclusion of children’s voice and participation as a national goal in the National Children’s Strategy 2000-2010 demonstrates the potential impact of national plans on children’s rights awareness and implementation. However, Lundy et al. (2013) caution that the role of a range of stakeholders, including UNICEF; national human rights’ organisations; non-governmental organisations; academics and the media, in documenting progress and auditing compliance is critical in sustaining progress towards full implementation. The UNCRC remains the most ratified international human rights treaty, ratified by all State Parties with the exception of the United States. With ratification comes a duty to implement the articles of the CRC. The four general principles summarised in Figure 15. underpin the Convention.

Figure 15. The Four General Principles Underpinning the UNCRC

The UNCRC adopts a holistic approach to the rights of children and brings economic, social, cultural, civil and political rights together in an integrated manner that reflects the full and harmonious development of the child’s personality and inherent dignity (Children’s Rights Alliance (CRA) 2010). The rights articulated in the UNCRC are not viewed as hierarchical but rather are designed to ‘interact with each other to form dynamic parts of an integrated unit’ (CRA 2010, 2). The principles articulated in Figure 14. underpin the development of the Universal Design Guidelines for Early Learning and Care settings, in terms of acknowledging children’s rights to an ELC environment that reflects these principles. Because ensuring participation of all children in high quality early years’ experiences is critical, specific emphasis is placed on Article 12 in the context of this project.

Article 12.1 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child states that:

State Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child (UN 1989: Article 12.1).

However, in accordance with the integration principle of the Convention, the participation rights in the CRC are also reflected across the Convention and particularly in Article 13 (Freedom of Expression); Article 14 (Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion); Article 15 (Freedom of Association and Peaceful Assembly) and Article 17 (Access to Information). These rights are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. Articles in the UNCRC Reflecting the Participation Rights Articulated in Article 12 (Adapted from UN 1989)

| Article 13 Freedom of Expression |

13.1 The child shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child’s choice. |

| Article 14 Freedom of Thought, Conscience and Religion |

14.1 State Parties shall respect the right of the child to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. 14.2 State Parties shall respect the rights and duties of parents and, where applicable, legal guardians, to provide direction to the child in the exercise of his or her right in a manner consistent with the evolving capacities of the child. |

| Article 15 Freedom of Association and Peaceful Assembly |

15.1 State Parties recognize the rights of the child to freedom of association and to freedom of peaceful assembly. |

| Article 17 – Access to Appropriate Information |

State Parties shall ensure that the child has access to information and material from a diversity of national and international sources, especially those aimed at the promotion of his or her social, spiritual and moral well-being and physical and mental health. |

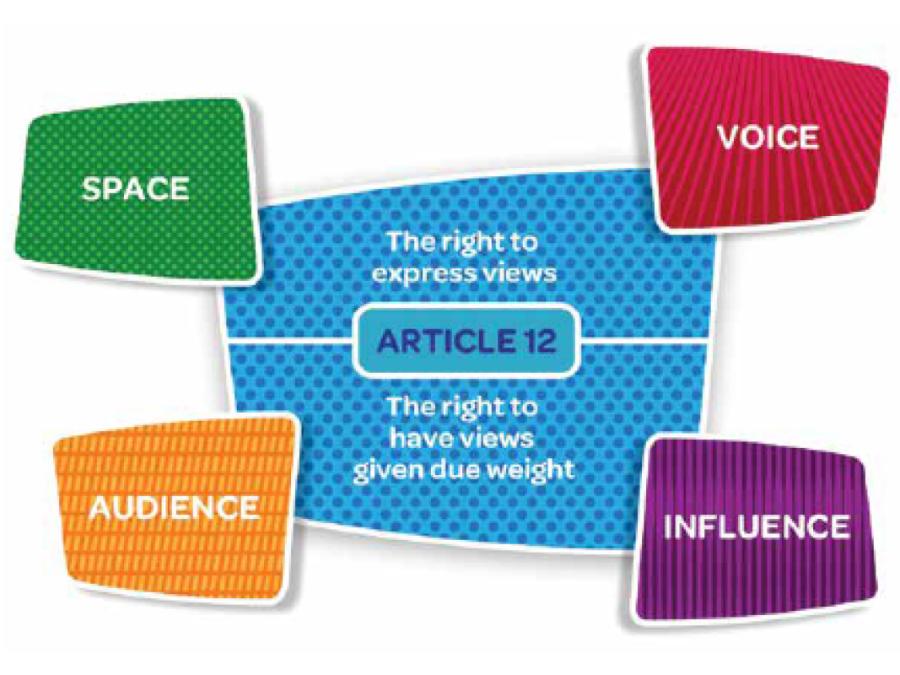

In the context of ensuring that children’s rights are central to the Universal Design Guidelines for Early Learning and Care settings, a focus is maintained on considering the implications for Universal Design in terms of providing for children’s participation with reference to the principles articulated in both Figure 14 and Table 4 in association with the range of related Irish policy and curriculum documents and the provisions of the UNCRPD (Ireland 2000; CECDE 2006; UN 2006; NCCA 2009; DCYA 2014, 2015; NCCA 2015; DCYA, 2016). Specifically the Lundy Model of Participation adopted by the DCYA in the National Strategy on Children and Young People’s Participation in Decision-Making (2015-2020) is useful in reflecting on how children’s participation is conceptualised and operationalised in ELC settings.

The model in Figure 16. suggests that children should be given space through the provision of safe and inclusive opportunities to both form and express their views; allocated a voice through being facilitated in expressing their views; ensure children’s voices are listened to by an audience and their views responded to in order that they understand that their views have influence.

Figure 16. The Lundy Model of Participation (DCYA 2015: 21)

Children’s rights and our responsibilities in considering Universal Design principles in ELC settings will be explored under the themes, which emerged from the synthesis of the literature: A Pedagogy of Voice and Freedom of Expression, Thought and Association.

3.3.1b A Pedagogy of Voice

Pedagogy can be described as how we teach, underpinned by the theories about how children learn and develop and our own beliefs and values about education (Jones and Shelton 2011). Our construct of children and on childhood is inextricably linked to the pedagogy we espouse. Influenced by the Italian Reggio Emilia approach, the image of the agentic child has emerged (Sorin, 2005). Childhood is recognised as a time of ‘being’ rather than ‘becoming’ when children adopt an active role in understanding their world through interaction with it (Ring and O’Sullivan, 2018). The adult’s role is concerned with guiding the learning process in collaboration with the child through the co-construction of knowledge (Sorin, 2005). ELC is concerned with the development of competent learners with high levels of motivation who are supported in applying their existing knowledge in new situations, to plan, monitor and evaluate their performance and demonstrate flexibility in strategy selection (Ring and O’Sullivan, 2018). The concept of the child as a citizen with rights and responsibilities, opinions worth listing to and a right to be involved in decisions affecting them is identified as one of the principles of Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework (NCCA, 2009). The agentic child is therefore a protagonist in a democratic early years’ system, which includes, listens to, and responds to all voices equally (Dewey 1916).

While including the voice of the child is articulated as a key principle of early years’ pedagogy, ensuring that a pedagogy of voice is central to the child’s experience in the early years continues to challenge education systems (Ring and O’Sullivan, 2016). Deegan poses the question as to whether we are truly convinced about the value of adopting a pedagogy of voice and critically, a pedagogy of listening. Landsdown (2005) observes that prioritising children’s participation impacts positively on children’s self-esteem and confidence; promotes their overall development; develops children’s sense of social competence, autonomy, independence and resilience. Subscribing to the principles of democracy in early learning and care places an intrinsic value on listening and responding to children’s voices, irrespective of a child’s age or ability (Rinaldi, 2012).

Gandini (2012) identifies a discernible connectedness between pedagogy and the architecture of the ELC setting, observing that on visiting a setting, the visitor reads the messages the space communicates between the quality of care and the educational choices that form the basis of the children’s experiences. The inclusion of children’s voices and how they are responded to is instantaneously evident in the spaces allocated to children’s creations; activities; expressions and photographs. Children’s sense of ownership and belonging is at once evident in the architecture and acoustic nature of the setting.

3.3.1c Freedom of Expression, Thought and Association

Creating an environment consonant with Article 3.1 of the UNCRC is central to securing children’s right to express themselves freely, including freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child’s choice (UN, 1989). In accordance with Article 14.1 and 15.1, in this environment, the child has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion and the right to freedom of association. Embedding the child’s access to information and material from a diversity of national and international sources, including those aimed at promoting the child’s social, spiritual, moral well-being, physical and mental health in this context provides for the realisation of Article 17. of the UNCRC (UN, 1989).

Communicating is one of the four themes of Aistear: The Early Childhood Curriculum Framework and is concerned with children being provided with enriched opportunities to share their experiences, thoughts, ideas and feelings with others in a variety of ways and for a variety of purposes (NCCA, 2009; 2015). Edwards et al. (2012) refer to the hundred languages of children and highlight the importance of children’s myriad of communication modes being responded to. Children communicate in diverse ways such as through facial expressions; gestures; body movements; sounds; art; music; dance; drama; photographs; symbols; assistive technology; signing, Braille and story (NCCA, 2009). The role of the adult is central to creating an environment where freedom of expression is promoted and which:

“....motivates children to interact with each other and the adult, and with the objects and places in it. By capturing children’s interests and curiosity and challenging them to explore and to share their adventures and discoveries with others, this environment can fuel their thinking, imagination and creativity, thereby enriching communication” (NCCA, 2009: 34).

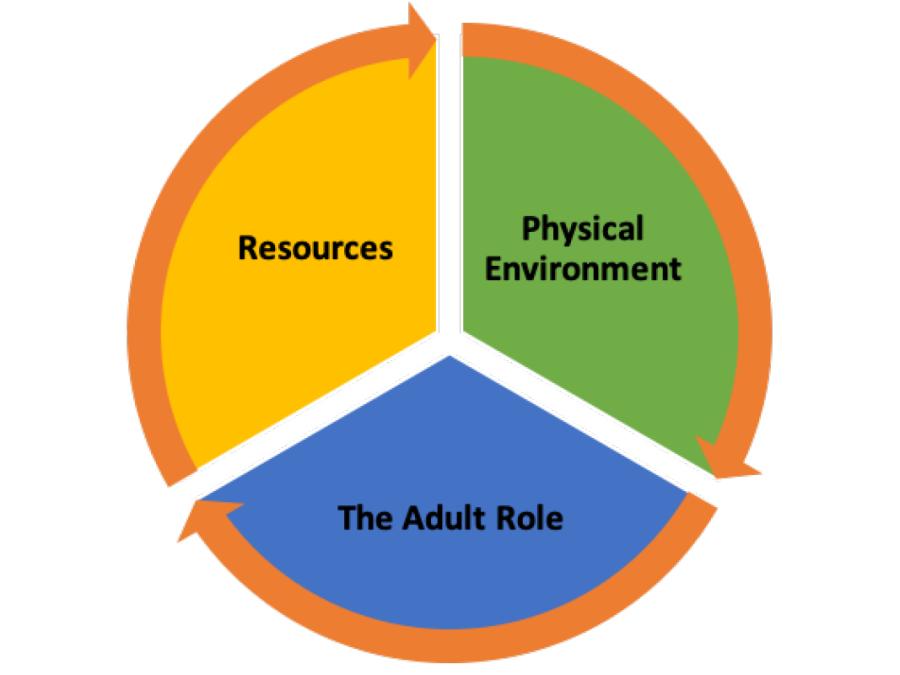

Jarman (2013) observes that developing children’s communication skills does not take place in isolation and emphasises the importance of providing a context within which to support children in assimilating and practising their new knowledge and skills. Jarman suggests adopting a Communication Friendly Spaces ApproachTM (CFSTM), which takes a holistic perspective of the learning environment and focuses on the three areas of the physical environment; resources and the adult role, working in harmony together, with no one area on its own being sufficient. See Figure 17. below adapted from Jarman (2013).

Figure 17. A Communication Friendly Spaces Approach adopted from Jarman (2013: 10)

The creation of a CFCTM provides a structure within which to provide for the child’s right to freedom of expression, thought and association. Jarman (2013) advises that attention should be directed towards the scale, quality, developmental appropriateness and purpose of resources. Gandini (2012) highlights the role of the physical environment in communicating to children and suggests that the structures, choices of materials and stimulating manner in which educators construct environments should be focused on creating an open invitation for children to explore and communicate, both individually and with each other. Gandini advises that encouraging physical conditions, the use of natural light and uncluttered spaces positively support and encourage children’s development. As noted by Gandini (2012), young children’s development is enhanced and optimised through sensorial explorations and the opportunity for children to construct their knowledge and memory through them. An environment which utilises colour, light, sound and smell and provides a rich and varied selection of materials with multi-sensory surfaces and features based on the observed preferences of individual children and commensurate with their developmental levels, supports children’s right to expression through encouraging them to seek, receive and impart information and ideas in motivational contexts (Zini, 2005).

The organisation and use of materials in the ELC setting impacts significantly on children’s experiences and are shaped by distinctive cultural, political, historical and social influences (Prochner et al., 2008). The importance of creating an inclusive physical environment is highlighted in the Diversity, Equality and Inclusion Charter and Guidelines for Early Childhood Care and Education (DCYA, 2016). While it is stressed that the interaction and discussion with the materials in the physical environment promote children’s understanding of difference, the guidelines highlight that the provision of a rich, diverse physical environment has an important role in promoting inclusion and supporting children in accommodating differences (DCYA, 2016).

Creating an environment, which fosters freedom of expression, thought and association and includes access to appropriate information is therefore both a possibility and a key responsibility for ELC settings.

3.3.2 Standard Three: The Child and Parents and Families

Valuing and involving parents and families requires a proactive partnership approach evidenced by a range of clearly stated, accessible and

implemented processes, policies and procedures. Interactions with parents and families is another important indicator of process quality in ELC as parental engagement in children’s early learning and care is associated with a range of positive socio-emotional and academic outcomes (Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). Strong setting-parent relationships provide children with continuity of experience between home and the ELC setting. When parents and families are involved in their children’s setting, children’s learning and development is promoted in an integrated and holistic way. Research undertaken in the UK by The Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) (2015), found that the most effective ELC settings worked as much with parents as with children which was found to be particularly beneficial in terms of supporting more vulnerable children and families.

Parents often see educational settings as the context in which learning takes place. This is ironic given that early learning is best nurtured through the type of informal and meaningful experiences which abound in the home environment (Whitebread, 2015). Engaging with parents and families also allows the ELC setting to surface each child’s unique cultural capital, upon which all new learning is built (Brooker, 2010; Whalley, 2017). Good communication with parents and families supports parental understanding of the curriculum - what the setting goals are for children’s learning and development and the principles and methodologies the setting uses to support children developing as competent and confident learners (NCCA, 2009). This is important, as parental views in relation to the content and processes of early learning are often not well aligned with those of the ELC setting (Brooker, 2010; Moyles, 2012). As parental awareness around what and how children are learning increases, so too does the likelihood that parents will further support children’s learning journey in the home environment through promoting talking, reading and playing (OECD, 2012; Whitebread, 2016; Fisher, 2018).

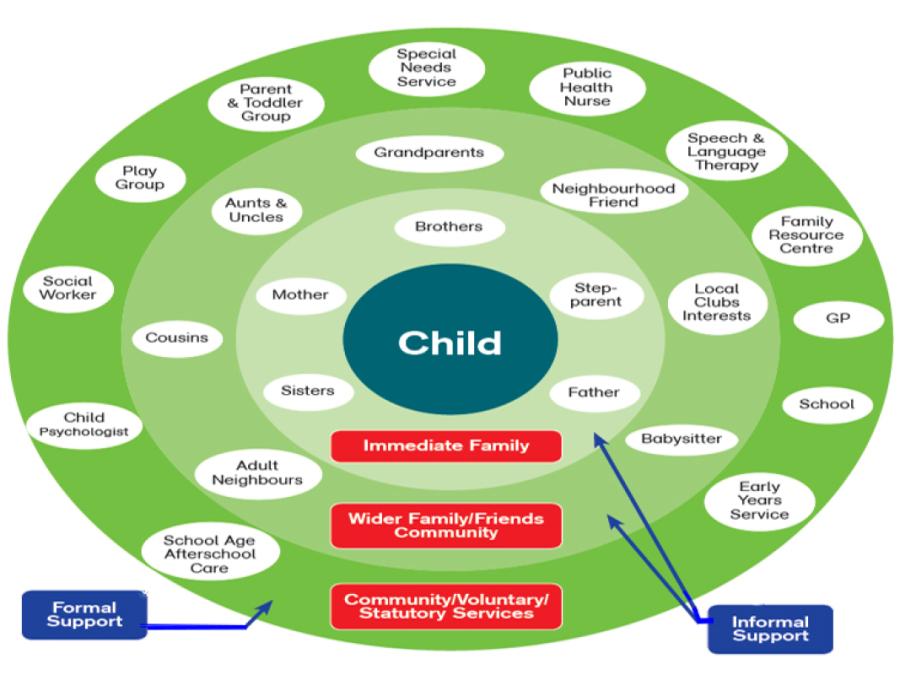

As parental working patterns continue to change, children are spending more time in ELC settings which further emphasises the salience of effective relationships with parents and families (OECD, 2012). Greenman (2007) points out that children who enter childcare during their first year can spend up to 12,000 hours in their ELC setting. Epstein’s (2014) Theory of Overlapping Spheres of Influences highlights the intersection between home, school and community in children’s learning and development. Epstein’s six types of involvement are empirically grounded and used internationally as a framework to support parental and family engagement in their children’s education:

- Communicating

- Volunteering

- Learning at home

- Understanding the child as student

- Decision making

- Collaborating with the community

In terms of promoting parental and family engagement it is important to consider how the environment can support these various types of involvement. Aistear (NCCA, 2009) and Síolta (CECDE, 2006) recognise that the environment should be inviting and welcoming for children and parents and that it should reflect each family’s cultural capital. The environment of the ELC setting has a responsibility to support children developing a strong sense of belonging to their families and communities in addition to the setting itself (NCCA, 2009). The Environment can support parents and families through promoting:

- A Sense of belonging

- Communication

- Engagement in play and learning activities

- Engagement in decision making

Greenman (2007), challenges us to view ELC settings not simply as settings for children but as settings for families.

3.3.2a A Sense of Belonging

The Early Learning and Care environment should be designed to be visible in the community and easily accessible to parents and families (Gandini, 2012; Burke et al., 2016). Richardson (2011) suggests that for some parents and families, experiencing a sense of belonging to the setting comes easier than others. The ELC setting might be more welcoming for parents and families who share the language and culture of the setting, for example. For parents and families where the language and culture are different to their own, the ELC setting might be a less welcoming space (Richardson, 2011). Simple measures such as including photos of families, communicates that each family is valued in the setting. Clearly pictures, resources and displays should be selected which reflect all cultures, not just the dominant mainstream culture in the setting (Brooker, 2010; Moyles, 2012; Fisher, 2018). Simple greeting messages which are often displayed at the entrance to ELC setting should be displayed in the family’s home language if it is not English. Parents’ and families initial contact with setting can set the stage for future interactions with the setting and staff (Ofsted, 2015; Fisher, 2018). Consequently, it is important that the environment, from the families very first contact with it, is enticing and inviting (Greenman, 2007; Gandini, 2012; Ofsted, 2015;Fisher, 2018). This is a definite prerequisite to increasing parental engagement during the child’s time in the setting (Better Start Resource Centre, 2011).

3.3.2b Communication

Families should be able to find their place in the ELC setting and there should be spaces which easily foster communication between parents, families and staff. Sharing of information between parents and the setting is generally a priority in terms of parental engagement (NCCA, 2009). Including a notice board or display which is regularly updated offers an accessible means of communicating easily with parents. Information can be included on curriculum activities or special events. Visual supports would, again, be important for parents who may have learning difficulties or who have English as a second language (NCCA, 2009; Fisher, 2018).

The environment also needs to accommodate routine communication during drop-off and pick up and perhaps more formally organised ELC practitioner- parent meetings (OECD, 2012). For more formal meetings, privacy is important for parents and families (Richardson, 2011). Rather than having to engage in discussions in busy, public spaces, the environment should incorporate a comfortable, safe space for ELC practitioners to meet with parents. Moreover, the environment can support parents building relationships with other parents and families when it provides space for parents to communicate and collaborate with each other (NCCA, 2009; Gandini, 2009). The environment can facilitate parents to linger and engage with each other through the provision of sofas or chairs in the entrance area as in the Reggio Emilia environments (Gandini, 2012).

Opportunities for parental education make an important contribution to children’s learning and development (Gandini, 2012; Ring and O’ Sullivan, 2017). Ring and colleagues (2016), for example, found that parents did not consider play as contributing significantly to early learning (Ring, et al., 2016). This suggests that ELC settings need to engage more with parents around how informal and playful learning conditions drive early learning (Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). Many measures, such as increases to non-contact time for staff, are needed if ELC practitioners are to invest more time in parent education initiatives (O’ Sullivan and Ring, 2018). Appropriate space and adequate resources (e.g. ICT resources), clearly play a part. Providing accessible, comfortable spaces for parent education activities will support parental understanding of the philosophy of the setting, in addition to encouraging them to continue to support their children’s learning in the home environment (Greenman, 2007; Gandini, 2012; Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015).

3.3.2c Engagement in Play and Learning Activities

The ELC environment can promote parental and family engagement through providing adequate space for parents and families to become directly involved in activities (Gandini, 2012; OECD, 2012; Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). Ideally the environment should be designed to facilitate more flexible parent involvement (Greenman, 2007). When children are transitioning to the ELC setting, for example, the environment should be able to accommodate them coming and going as they feel necessary (Greenman, 2007). Parents might volunteer to provide additional support during child-initiated activities or to develop an experience for children based on their own interests and expertise (Fisher, 2018). In Reggio Emilia pre-schools each child’s parents are invited to spend a day in the pre-school (Gandini, 2012). Working with parents as volunteers rather than clients can help parents to aspire to have high expectations for their children which in turn is related to children’s achievement (OECD, 2012). Including space and resources for initiatives such as a toy, games and a book sharing library can also increase parental participation within the setting and in their children’s learning (Fisher, 2018).

Just as it is important to have spaces which accommodate all learners in the community to come together, these spaces should also be large enough to include families, children and staff coming together for events such as celebrations and performances (Gandini, 2012; Burke et al., 2016). It might not just be parents and siblings who want to join in celebrations but also grandparents, aunts, uncles etc. Moreover, the extended family might be more involved in child-rearing for families from more collectivist cultures than they are in families from individualist cultures (Maschinot, 2008).

3.3.2d Engagement in Decision Making

The extent to which parents become involved in decision making can vary and might involve engaging informally through day to day dialogue, through becoming involved in a parents’ association or through sitting on a management board (Barnardos, 2006). According to Barnardos (2006, p.9), “Effective programmes encourage parents to become actively involved in the decision-making process within the setting. This involvement helps to develop positive partnerships between parents and staff and increases parents’ understanding of how the setting operates”.

In the Reggio Emilia pre-schools of Northern Italy, for example, parents are highly involved in the governance of the pre-schools (Gandini, 2012). In addition to contributing to decisions about the running of the service, policy, curriculum and pedagogy, parents can also contribute to decision making in respect of the learning environment. There should be opportunities, both formal and informal, to include parents and families in decision making in relation to the environment (OECD, 2012; Burke et al., 2016). As ELC settings aim to become more inclusive for all learners and their families, parents can provide invaluable input in terms of how the home culture organises the environment to support learning (Brooker, 2010).

Parents can also be an invaluable source for resources. If the setting requires resources for a particular project or play area, then parents may often be in a position to contribute or to support fundraising initiatives, for example (NCCA, 2009). As Gandini (2012) points out, when parents are engaged in decision making, ideas are exchanged and new ways of educating are constructed. Providing opportunities for parents and families to become involved in decision making can help parents transition from more peripheral to full engagement with the setting (Best Start Resource Centre, 2011).

3.3.3 Standard Five: The Child and Interactions

Fostering constructive interactions (child/child, child/adult and adult/adult) requires explicit policies, procedures and practice that emphasise the value of process and are based on mutual respect, equal partnership and sensitivity. Quality ELC is frequently articulated in terms of its structural and process features. Process quality is a dynamic construct and includes the interactions between children and adults and between children themselves. Process quality has been found to have a stronger association with child outcomes (NICHD, 2006). Interactions, therefore, have a salient influence on children’s learning and development in the early years (Melhuish et al., 2015). According to the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2004, p. 2), “children who develop warm, positive relationships with their kindergarten teachers are more excited about learning, more positive about coming to school, more self-confident, and achieve more in the classroom”. In the Irish co text, both Aistear (NCCA, 2009) and Síolta (CECDE, 2006), recognise interactions as a key feature of high quality ELC. Consequently, the ELC environment should consider how:

- Interactions promote emotional warmth and security.

- Interactions promote play and learning.

- Interactions with peers support play and learning.

3.3.3a Interactions Promote Emotional Warmth and Security

An essential feature of interactions in the early years is providing children with emotional warmth and security (Whitebread and Coltman, 2011). This resonates with Deci and Ryan’s (2008) ideas in relation to the innate human need to feel connected to others. From an attachment theory perspective, warm, secure relationships are considered fundamental. Young children need to have their attachment needs met in order to become active players and learners (Howes, 2011). Children who do not feel emotionally secure in their ELC setting are unlikely to try out new activities and may have difficulty persevering when they encounter challenges (Whitebread, Dawkins, Bingham, Rhodes and Hemming, 2015).

Careful consideration should be given to the environment from which the child is transitioning (Whitebread et al., 2015). Many children may be coming from home to the setting and it is important to make connections between these two environments. As the home environment will ge erally be the environment young children feel most secure in, ELC settings can benefit from including features more common in a home environment. Kitchen and dining areas, for example, could be organised to allow for frequent, responsive interactions between adults and children during mealtimes, as might occur in the home environment. Creating a cooking and dining experience which mirrors that of a nurturing home environment is a key aspect of the Reggio Emilia approach where children are invited to join cooks to prepare meals and organise the dining experience (Gandini, 2012). Whitebread and colleagues (2015, p.30), illustration of a child articulating that “our classroom is like a little cosy house” perfectly captures how the environment can promote feelings of warmth and security for young children. To encourage interactions which support emotional warmth and security, there needs to be adequate space for adults to operate at the child’s level - adults need to be able to join children easily during play and routine activities such as mealtimes (Greenman, 2007).

In addition to various areas for specific activities, the inclusion of a quiet space where adults and children can easily connect, without distraction, is important. A child who is upset and needs comforting, for example, should have a calm space where they can easily connect with their key-worker. Regular settings can contain many environmental obstacles to children’s learning (Ring, McKenna and Wall, 2014). Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), for example, can be incredibly sensitive to sensory input from the environment and successful engagement in learning can be dependent on adult interactions which provide children with the emotional support they need to effectively process environmental stimuli (Mastrangelo, 2009; Ring et al., 2014). A further issue in terms of promoting emotional warmth and security is the extent to which the environment is organised to support children’s interaction with siblings if they attend the same ELC setting. Children can often spend long days in the setting without ever having interacted with their siblings who are in other rooms (Greenman, 2007). Clearly, when the environment affords opportunities for siblings to come together, all children’s feelings of warmth and security are supported.

3.3.3b Interactions Support Play and Learning

In Ireland and elsewhere, policy makers, educators and parents all emphasise emotionally warm and secure interactions as critical to children’s well-being (OECD, 2012; CARE, 2015; Whitebread et al., 2015). In addition to promoting emotional warmth and security, the research suggests that high quality interactions between children and adults also need to foster children’s learning (Fuller, Anguiano and Gasko, 2012; Pianta, Hamre and Allen, 2012; Pino-Pasternak et al., 2010; CARE, 2015). As part of the Curriculum and Quality Analysis and Impact Review of European Early Childhood Education and Care (CARE), the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS) was used to evaluate classroom quality across seven European countries. Classroom practices across these countries all scored high on social-emotional process quality but in the mid-range on the educational dimensions of CLASS (CARE, 2015). Interactions which support the educational dimension of children’s experience generally tend to support children’s feelings of control, provide cognitive challenge and stimulate articulation of learning (Whitebread and Coltman, 2011).

A well-organised environment is, perhaps, more important in a climate which promotes child-initiated play and learning than in a more traditional instructional context which is more tightly controlled by adults. Interactions which support children’s feelings of control will enhance children’s sense of ownership of their own learning and of their learning environment. When adults give children control over activities, this ensures activities are meaningful and connected to their interests, resulting in more effective learning (Pino-Pasternak et al., 2014). When children have easy access to resources and when they are offered a genuine choice of activities, adult interactions can focus on encouraging children to do things independently rather than adults doing things for children (Whitebread et al., 2015). When the environment is flexible, rather than static, interactions stimulate dialogue with children around their emerging interests and adapt the environment to respond to these interests. As suggested by Howard and McInnes (2013, p. 66), children should have an environment in which they are “able to form and transform at will”. When the environment is well organised children can independently go about the business of playing and learning. Adult interactions can extend learning rather than devoting excessive amounts of time to setting management (Whitebread, et al, 2015).

Cognitive challenge involves interactions which provide achievable challenge with appropriate support through experiences such as child-initiated play. Young children are immensely open to new experiences and providing appropriate levels of cognitive challenge will encourage effective learning. Approaches identified in the research as being effective in providing adequate cognitive challenge include Sustained Shared Thinking (SST) (Siraj-Blatchford and Sylva, 2004) and contingent scaffolding (Pino-Pasternak, et. al, 2014). To engage in interactions which provide cognitive challenge, at a basic level adults need to be able to interact easily with children. While Montessori’s influence can be seen in the proliferation of child scaled environments in childcare settings, Greenman (2007, p. 82) argues that “a mixture of adult and child scale is valuable for both caring and learning and minimises the teacher as an outsized Gulliver in a Lilliputian world”.

While consistency and predictability are important for promoting emotional warmth and security, young children also need new experiences to satisfy their innate curiosity and drive to understand how the world works. Adults need to carefully plan, based on interests, how the environment can be used to provide the type of challenging experiences which allow children to build on prior learning, make connections and to construct new learning. Arnold (2015) provides a wonderful overview of how one reception classroom in the UK facilitated children learning about the life-cycle of a chicken. As part of this learning experience an incubator and eggs where hired to provide the children with meaningful first hand learning opportunities. The presence of the incubator in the immediate classroom environment proved to be an important source of learning over an extended period as children, in collaboration with adults, monitored the hatching chicks (Arnold, 2015). Sargent (2011), adopting the idea of ‘provocation’ from Reggio Emilia, discusses how the environment can be organised in a way in which objects or pictures can be used to provoke inquiry- based learning. To provoke thinking on the topic of minibeasts, for example, she describes how a paper-mâché cocoon with a minibeast toy inside was attached to the classroom ceiling and the adults waited for the children to notice this new arrival. Adults then, through making suggestions and asking open-ended questions were enabled to facilitate sustained shared learning across a number

of weeks (Sargent, 2011).

Articulation of learning which involves children engaging in reflection and extended conversations about their learning has been highlighted as an important feature of interventions designed to positively impact on learning and development (Whitebread and Coltman, 2015). The High Scope Curriculum (Schweinhart, et al., 2005), for example, encourages this type of articulation of learning through its plan-do-review component and play-planning is also a key feature of the Tools of the Mind Curriculum (Bodrova and Leong, 2007). Interestingly, both these models are associated with a range of socio-emotional and cognitve outcomes (Schweinhart et al., 2005; Blair and Raver, 2014).

The environment can support children to articulate their learning in a number of ways. At the most fundamental level, we can draw children’s attention to aspects of the environment and resources which foster new and deep learning. While children are multi-modal communicators, during the preschool years, encouraging children to verbally articulate their learning is a key curriculum priority. Consequently, the environment needs to foster dialogue and verbal communication. Jarman’s (2015) Communication Friendly SpacesTM (CFSTM) approach focuses on how the environment supports talking, listening and children’s overall engagement in learning. This approach encourages adults to reflect on traditional ideas in relation to how we design environments in terms of how responsive they are to children’s learning needs. The approach

draws heavily on Reggio Emilia philosophy and challenges ideas in relation to colour schemes, room layout, displays and quantity of learning resources. Observation and assessment are at the heart of the CFSTM approach and adults are encouraged to consider how the environment might potentiate or inhibit communication from the child’s perspective.

Drawing again on Reggio Emilia philosophy (Edwards, Gandini and Foreman, 2012) and Gardner’s (2004) ideas on Multiple-Intelligences (MI), children can articulate their learning in an infinite number of ways. The environment needs to provide opportunities for children to share their learning with adults, through language but also through various visual media and play types (Gandini, 2012). Displays are another aspect of the environment through which children can articulate their learning. Displays support learning when they have a clear purpose for children, when children have ownership over what is displayed and when displays are interactive (Whitebread et al., 2015). Adults should endeavour to interact with children continually around how displays are used in their room.

3.3.3c Interactions with Peers Support Play and Learning

While children need to experience learning opportunities which are sensitively guided by adults, they also need to experience freedom (Burke, Barfield & Peacock, 2016). Freedom, in particular, to interact with peers is a key source of learning in the early years. The CARE (2015) review of childcare across 7 European countries identified a focus on dyadic interactions between adults and children which, they recommend, needs to be balanced with a stronger focus on the peer group itself as a community of learners (CARE, 2015). Primarily, when children have opportunities to learn independently, they create what Vygotsky referred to as a unique Zone of Proximal Development’ (ZPD) where the group collectively acts as a more knowledgeable other (Bodrova and Leong, 2015). For nthese reasons, opportunities for independent play and activities with peers are conducive to many of the goals of early learning and care such as developing self-regulation, social competence, friendships, language and creativity (Rubstov and Yudina, 2010; Weisberg, Kittredge, Hirsh-Pasek, Michnick Golinkoff and Klahr, 2015). Independent activity with peers affords children the opportunity and space to lead their own learning. In many classroom activities adults can assume the regulatory role, potentially reducing the opportunity for children to regulate their own behaviour and interactions and to follow their own creative processes (Whitebread, 2012; O ‘Sullivan, 2016; Gray, 2015). As suggested by Rubstov and Yudina (2010), while play might be free for the child, it is not so free for the ELC practitioner, who must ensure that it remains free. ELC practitioners and ELC designers, therefore, need to consider how the environment can be designed and organised to maximise interactions between peers.

Firstly, if the aim is to encourage more independent play with peers and adults, while taking a less active role in interactions, adults still need to be able to easily supervise children’s interactions with each other. Adults need to be able to see any potential safety issues and easily identify scenarios where they might be needed to mediate in interactions between peers (Jones and Reynolds, 2011). Children have different ways of interacting with their peers and the environment needs to take cognisance of this (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004).

UNICEF (2014) emphasises the need for child-friendly environments to be gender-sensitive, ensuring both boys and girls have equitable opportunities to learn and develop to their full potential. Recognising and responding to the interactional styles of boys and girls is important in creating ELC settings which are gender-sensitive. The research suggests patterns in terms of how boys and girls interact with others. Boys often prefer to play in more open spaces, in larger groups and further away from adults whereas girls often prefer to play in quieter areas, in smaller groups and in closer proximity to adults (Martin et al., 2011; Frost et al., 2012). To facilitate the interactional preferences of boys and girls, the environment should include large open spaces and more intimate smaller mspaces.

Culture can also influence children’s interactional patterns. Trawick-Smith (2010), in a study of play in a Puerto Rican preschool found that children tended to play in very large groups, often with up to twelve children, and with little adult involvement. In other contexts, children might demonstrate more of a preference for dyadic or triadic interactions. Careful observation will allow adults to adapt the environment based on children’s preferences. Moreover, the environment can be adapted to facilitate interactions. Where boys and girls may be less inclined to play with each other, creating play and activity centres which incorporate the interests of boys and girls has been found to increase mixed sex interactions (Johnson et al., 2005; Frost et al., 2012; Moyles, 2012). Similarly, where children experience different ways of play and learning in their home cultures, simple environment or resource modifications can support their transition to the ways of play and learning promoted in the setting (Brooker, 2010; Moyles, 2012).

The setting needs to take cognisance of how the environment can support peer interactions for children with additional needs. Children with additional needs have been found to spend more time engaged in solitary activities and more time interacting with adults than peers (Brown & Bergen, 2002). On an individual basis, the setting should be evaluated to investigate how the environment may be hindering or supporting children with additional needs interacting with peers. For some, it may involve looking at how the environment can support communication, for others it may involve looking at how the environment can support full access to, and participation in, various play areas and activities.

Gray (2013) presents a solid argument for the role of mixed aged groupings in fostering children’s learning. This resonates with Montessori who also emphasised the mixed age groups as a context for peer scaffolding and for developing leadership dispositions (Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). A recent small-scale comparative study on mixed-age groupings of children aged three-to-five years in Ireland and Italy highlighted all ELC practitioners beliefs that mixed-age groupings contribute significantly to children’s social and emotional development and their communication and language skill (McCarthy, 2017). As it is generally the case in Ireland that children are grouped based on age in ELC settings, the environment can support interactions between children in different classrooms through providing shared spaces where children from different rooms can come together (Burke et al., 2016). This is similar to the need for the environment to foster emotional warmth and security through supporting interactions between siblings in the childcare setting (Greenman, 2007). Such spaces may be outdoors, involve a communal area indoors or a dining space (Burke et al., 2016).

Burke and colleagues (2016) discuss the importance of the environment having a ‘heart’. At the heart of the environment should be a place where everyone in the setting can easily come together. This resonates with the Reggio Emilia concept of the ‘Piazza’, a centrally located communal space (Gandini, 2012). The inclusion of glass walls or partitions can nurture interactions with children outside of the immediate classroom environment (Gandini, 2012).

3.3.4 Standard Six: The Child and Play

Promoting play requires that each child has ample time to engage in freely available and accessible, developmentally appropriate and well-resourced opportunities for exploration, creativity and ‘meaning making’ in the company of other children, with participating and supportive adults and alone, where appropriate.

Congruent with developments internationally, in Ireland, play is recognised as a key context through which young children learn and develop (NCCA, 2009). Play is best conceptualised as a motive or attitude (rather than a behaviour per se) which is characterised by autonomy, a focus on means over ends, internal rules, imagination and an active non-stressed mind-set (Gray, 2013). For play to optimally support learning and development it is crucial that children have choice, that activities are intrinsically motivating, provide opportunities for them to make up their own rules and to use their imagination. When learning experiences foster these features of play or playfulness children learn in an active and non-stressed manner, which is associated with optimal learning (Gray, 2013; Ring & O’ Sullivan, 2018). A growing corpus of research endorses the view that playful conditions have a differential impact on learning and development. Play has been associated with gains in problem-solving (Thomas, Howard & Miles, 2006), language (Weisberg, Zosh, Hirsh-Pasek and Michnick Golinkoff, 2013), mathematical understanding (Wolfgang, Stannard and Jones, 2003) and various measures of self-regulation (Gayler & Evans, 2001; Becker, McClelland, Loprinzi, and Trost, 2014; O’ Sullivan, 2016).

As the empirical basis for playful learning continues to grow, play has become more centrally located within the early years curriculum. Consequently, it has become increasingly necessary to create ELC environments which provide opportunities for children to develop complex and sustained play. The play and learning environment is a key feature of structural quality with the overall quality of the child’s learning environment strongly linked with learning outcomes (OECD, 2012; Melhuish et al., 2015). The play environment can promote, to varying degrees: children’s interests, identity and belonging, interactions, self-regulation, language and communication, and a range of thinking and problem-solving behaviours (Whitebread et al., 2015). Consistent with this view, Loris Malaguzzi located the environment at the core of his philosophy and consequently the environment is known as “the third teacher” within the Reggio Emilia approach (Gandini 2012). For the purposes of the present review, the play environment will be discussed in respect of:

- Facilitating diverse play opportunities,

- The indoor play environment,

- The outdoor play environment,

- Toys and play materials,

- Collaborating with children around the design of their play environment.

3.3.4a Facilitating a Diverse Range of Play Opportunities

Aistear (NCCA, 2009), Síolta (CECDE, 2006) and The Quality Framework for Early Years Education-focused Inspections (DES, 2018) all acknowledge the need to provide children with a well-resourced diet of play opportunities to ensure play is a central mechanism through which children learn and develop. Children benefit from a broad range of play experiences including physical play (active exercise play, rough and tumble play, and fine-motor practice), object play (exploring and experimenting, constructing and making), symbolic play (with language, music, visual media reading, writing and mathematical graphics), pretend play and games with rules (Whitebread, Basilio, Kuvalja and Verma, 2012). These five types of play can be solitary or social, child-initiated or adult-guided and can occur indoors or outdoors. Moreover, these five categories of play are not mutually exclusive. Trawick-Smith’s (2010) concept of ‘primary play’ and ‘embedded play’ reflects the tendency of children to transition between different types of play. In terms of play provision, it is also important that children have opportunities to learn through child-initiated play and sensitive adult-guided play (OECD, 2012; Weisberg et al., 2015; O’ Sullivan and Ring, 2018). Having autonomy is a key feature of playful learning and as such, creating an environment which supports children to lead their own learning should be a priority. Children will certainly struggle to be active learners who lead their own play if the environment is difficult to navigate and toys and play materials cannot be sourced independently. While child-initiated play is conducive to many of the goals of early childhood such as developing self-regulation, social competence, creative and problem-solving, the research also highlights the significance of adult-guided play for learning (Weisberg et al., 2015; Whitebread et al., 2015). In the absence of guided play, children might not spontaneously access important curriculum content. When adults become sensitively engaged as co-players, they can provide emotional warmth and security, cognitive challenge and model rich vocabulary and explanations. This type of involvement has been found to enhance, rather than marginalise, children’s learning through play (Trawick- Smith and Dziurgot, 2011; Whitebread and Coltman, 2011; Weisberg et al, 2015). Consequently, the play environment also needs to be a place which is inviting, comfortable and accessible for adults (Greenman, 2007).

3.3.4b The Indoor Play Environment

At the most basic level, children require adequate space to play. Adequate space reduces stress and promotes well-being which is pre-requisite to effective playing and learning (Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). The minimum space requirements for ELC settings are set out in The Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016 (DCYA, 2016). All registered services providing the universal pre-school programme (ECCE scheme) must provide a minimum of 1.8sq metres per child (2.3 sq. metres after scheme hours). In a review of quality early childhood education Whitebread and colleagues (2015) found that well designed spaces were associated with more positive interactions and more time spent exploring the environment. A high quality play environment should provide areas or zones which offer specific play experiences and spaces for children to make their own (Frost, Wortham and Reifel, 2012). Such areas encourage independence as children will know what experiences are afforded in various centres. Montessori strongly advocated for a prepared environment which she saw as critical to fostering independence in learning (Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). Children will learn where things are and recognise boundaries and how areas are separated (NCCA, 2015). ELC settings often include areas for:

- Pretend play

- Music

- Visual media

- Sand and water

- Constructing and making

- Book sharing

- Writing/ mark making

- Quiet activities.

A consideration is the extent to which areas are conflicting or complimentary. It might not be most effective, for example, to position a busy area, such as constructing and making, right beside an area for quieter activities. An option is to partition off certain areas to encourage sustained and complex play (Frost et al., 2012). While more closed and designated spaces can support play, children benefit from an environment which incorporates more fluid open spaces (Frost et al., 2012; Howard and McInnes, 2013). Open spaces allow for children to come together in bigger groups and to select and combine materials from various areas. While children can benefit from having specific areas which provide specific play opportunities, it is also important to include spaces which children can make their own. Broadhead (2010, p.46) describes creating what one child described as “the whatever you want it to be place”. Her research suggests that the provision of a more open-ended space led to high levels of collaboration and more complex play as ‘an anything you want it to be place’ did not suggest

any one way of playing (Broadhead, 2010). Consideration should also be given to how children move between play/activity areas. Undertaking a movement or flow chart can give important information as to how the environment is being used and the pathways children take between different play areas (Johnson, Christie and Wardle, 2005; Greenman, 2007). If certain areas are over or under used then adults can plan how the environment can be altered to support pathways between certain areas. As set out in The Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016 (DCYA, 2016), children require access to quieter spaces in which they can engage in self-initiated activities such as reading or listening to music. In addition to considering how the environment can provide for the main types of play, consideration should also be given to how the play environment supports more quieter and solitary play experiences in addition to small and large group play

(Greenman, 2007). Children play and learn everywhere. Trawick-Smith (2010) found in his study of play in Puerto Rican preschools that play often occurred in unexpected places rather than in the areas designed for specific play types. This suggests that observation of children’s interaction with their play environment is critical to the provision of high quality play. Interaction with the play environment will most likely change between different cohorts and among the same cohort over the duration of their time in the setting. Moreover, as childcare settings continue to embrace diverse learners, a once size fits all environment becomes less tenable. Children who have language, visual or hearing challenges, for example, will all require tailored supports to independently navigate their play environment (Greenman, 2007; Howard and McInnes, 2013).

3.3.4c The Outdoor Play Environment

Western industrialised countries such as Ireland have traditionally focused more on developing indoor rather than outdoor play environments. This is in contrast to Scandinavian countries where there is a strong tradition of playing and learning outdoors. There is a recognition that high quality early learning and care is best facilitated through balancing opportunities to learn indoors with opportunities to learn outside (OECD, 2012). Consequently, The Child Care Act 1991 (Early Years Services) Regulations 2016 (DCYA, 2016) now require services registered before June 2016 to have a suitable, safe and secure outdoor space (on or off the premises) accessible to the children daily and for those registered after June 2016, this outdoor space must be available on the premises. The indoor and outdoor learning environments are essential to promoting learning and development. Indoor and outdoor play spaces should be complimentary and integrated, and should aim for flow rather than separation (Johnson, Christie and Wardle, 2005; Greenman, 2007; Frost et al., 2012). Moreover, every room in the ELC setting should have easy access to the outdoor environment, ideally a direct level connection (Burke et al., 2016).

Tovey (2007), challenges educators to reflect on whether the outdoor area is simply a physical space or a place which is meaningful for children. All types of play can just as easily be facilitated outdoors as well as indoors. The outdoor environment can be more conducive to physical play, allows for construction on a larger scale and provides a range of natural materials for children to transform, explore, experiment with and to design and make with. A key affordance of the outdoor play environment is its dynamic quality (Tovey, 2007). Weather alone can lead to the same space being transformed overnight, grass which was wet and muddy can suddenly become hard and cold after a spell of frost. The Forest School Approach, initially developed in Scandinavia, is now gaining momentum across Europe. The Forest School Approach places a strong emphasis on experiential learning through direct contact with nature in woodland settings (Knight, 2011). The promotion of this type of child-initiated experiential learning outdoors is believed to foster well-being through affording opportunities to connect with nature and others, problem-solving and risk-taking (Knight, 2011: Moyles, 2012). While The Forest School Approach has its own distinct content and methodologies, it is clear that all early learning environments can be enriched through providing opportunities for children to engage with the natural world in an experiential and playful way. In the new Cambridge University Primary School, nursery and reception classrooms have access to a wild wood in their playground (Burke et al., 2016).

A high quality outdoor play environment requires careful planning similar to the indoor environment. Tovey (2007) recommends that an ideal outdoor learning environment should have the following features:

- Designated and connected spaces

- Elevated spaces

- Wild spaces

- Spaces for exploring & investigating

- Spaces for mystery & enchantment

- Natural spaces

- Space for the imagination

- Space for movement & stillness

- Social spaces

- Fluid spaces

While risk taking can be considered a feature of all play experiences, the outdoor play environment is particularly conducive to allowing children engage in risk taking as, according to Tovey (2010, p.80-81), such play can “thrive in the more open, flexible, diverse and indeterminate nature of the outdoor environment where children have greater space, freedom of movement, choice and control”. In an ELC setting a culture of risk aversion rather than of risk promotion often dominates (Tovey, 2010). Research undertaken by Sandseter (2007), in Norwegian preschools generated 6 categories of play in which children engaged and promoted risk taking behaviours:

- Play with great heights

- Play with high speed

- Play with harmful tools

- Play near dangerous elements

- Rough-and-tumble play

- Play where the children can ‘disappear’/get lost

A key challenge when creating high quality outdoor play environments is balancing children’s safety with their needs to explore, experiment and challenge themselves (Sandseter, 2007; Tovey, 2010). As Tovey (2007) suggests, we should strive to promote environments that are “safe enough” rather than as “safe as possible” to avoid creating environments which are underwhelming and under stimulating, leading to disengagement from learning and feelings of incompetence (Tovey, 2007; Howard and McInnes, 2013). Given that climate is often identified as a barrier to facilitating play outdoors, a covered outdoor play area can be invaluable in allowing children to play outdoors irrespective of weather conditions (Frost et al., 2012; Burke at al., 2016).

3.3.4d Toys and Play Materials

Within the ELC environment, play opportunities should be freely available, accessible, appropriate and well-resourced (DES, 2018). Toys and play materials can have a profound influence on the quality of children’s play as approximately 90% of young children’s play involves some type of toy or play material (Trawick- Smith Russell and Swaminathan, 2010). Toys and play materials can influence the social, emotional and cognitive affordances of play and the quantity and quality of available materials requires careful consideration. While providing plenty of choice is important, Howard and McInnes (2013, p. 66) rightly caution that a “room packed with equipment might look attractive and well-resourced but may not leave any scope for real playing to take place”.

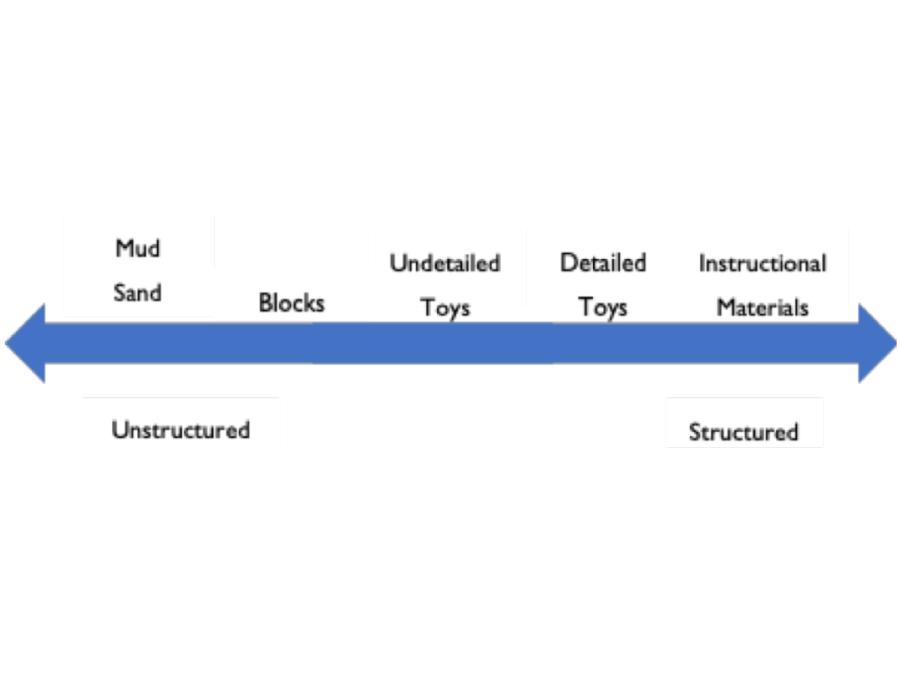

As illustrated in Figure 18., when selecting toys and play materials, it is important to balance structured materials such as puzzles or character toys with more unstructured or open-ended materials such as featureless toys and loose parts (Johnson, Christie and Wardle, 2005).

Figure 18. Continuum of Toys and Play Materials (Johnson, Christie and Wardle, 2005)

Materials which are more open-ended and suggest many possible uses are increasingly associated with high quality learning (Expert Advisory Panel on Quality Early Childhood Education and Care, 2009; Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). The philosophies of Steiner and Malaguzzi have emphasised the benefits of more natural toys and play materials for children’s learning and development (Howard and Mc Innes, 2013). The pioneering work of Goldschmeid and Jackson (1994), on the affordances of Treasure Baskets and Heuristic Play, has also inspired settings to give natural materials a more dominant role in the environment. Natural materials offer more possibilities as they have multiple uses and consequently inspire a range of creative and problem solving behaviours (Greenman, 2007; Howard and McInnes, 2013). When organising the environment it is important to facilitate children using materials from various areas, given that the fluid nature of play can lead to one type of play being embedded in another (Trawick-Smith, 2010).

The environment needs to balance young children’s need to revisit favoured play materials with their need for new and novel experiences. This can be achieved through rotating materials and introducing new materials. Children are not always drawn to materials that are most beneficial for development. Consequently, practitioners should not only observe what children are playing with but also what they do with materials when playing with them (Trawick- Smith, Wolff, Koschel and Vallarelli, 2014). Trawick-Smith and colleagues (2010), at the Center for Early Childhood Education, Eastern Connecticut State University are conducting an ongoing empirical study on preschool children’s engagement with toys and play materials, the TIMPANI (Toys that Inspire Mindful Play and Nurture Imagination) Toy Study. This research suggests that toys and play materials should be evaluated in terms of their potential to promote:

- Thinking and learning behaviours (e.g. studying objects/commenting on new concepts/discoveries)

- Problem-solving behaviours (e.g. overcoming challenge)

- Curiosity and inquiry behaviours (e.g. engaging in exploration/ experimentation)

- Sustained interest (e.g. persisting)

- Creative expression (e.g. using toys in novel ways)

- Symbolic transformations (e.g. making one thing represent another)

- Interacting, communicating, and collaborating with peers

- Autonomous play with toys (e.g. without adult assistance)

Recent research suggests that a one size fits all approach to the provision of toys and play materials may be inadequate. Trawick-Smith and colleagues (2015) in a study of the effects of toys on the play quality of preschool children found that boys and girls engaged with the same toys in different ways. The findings from this research suggest that some toys were associated with higher quality play for boys and others for girls (Trawick-Smith et al., 2014).

Culture is also recognised as having an influence on children’s play and it is not surprising that in this research children from different cultures engaged in play of varying complexity with the same toys. According to Trawick-Smith and colleagues (2014:6), this reflects “cultural differences in family play experiences, social and thinking styles, and even world views”. Some toys were used in a more complex way when used by Latino children and others when used by Euro-American children (Trawick-Smith et al., 2014). Similar results were found for children from varying socio-economic groups with some toys eliciting higher quality play for children from lower socio-economic groups and others for children from middle socio-economic groups (Trawick-Smith et al., 2014). As concluded by the authors, the most critical implication of this research is that “teachers must be observant, reflective, and responsive to individual children’s needs as they equip their classrooms with toys, just as they are in all other aspects of teaching” (Tawick-Smith et al., 2014).

Storage of toys and play materials is another important aspect of the play environment (Greenman, 2007; NCCA, 2015). Ideally, children should be able to access toys and materials independently of adults. In the tradition of Montessori, when children can do this, they are empowered to make decisions and take responsibility for their own play and learning (Whitebread, Kuvalja and O’ Connor, 2015). It is also important that children can return to favoured toys and play materials and that they have opportunities to preserve works in progress (such as a block construction ), if they need to (Whitebread et al., 2015).

The outdoor play environment offers unique affordances in terms of readily available natural play materials which allow children take responsibility for building their own play environment (Whitebread et al., 2015). Traditional play activities such as ‘den making’ are highly attractive to children, encourage engagement with natural materials and loose parts, inspire various types of play such as constructing and pretense, and encourage collaboration between peers as children use materials to build their own play environments (Brock, Dodds, Jarvis, and Olusoga, 2009).

3.3.4e Collaborating with Children around the Design of their Play Environment

The research suggests that children are often excluded from decision making around play, as adults do not appreciate their competence to contribute (Lester and Russell, 2008). Initiatives such as The Guardian newspaper’s “School I’d Like” survey and resulting Children’s Manifesto (Birkett, 2011), clearly demonstrate children’s capacity to articulate their preferences when it comes to the learning environment. Children surveyed made many references to the physical environment. Suggested features of an ideal physical environment include features such as lots of colour, fountains and glass domes, climbing frames, tree houses and rock-climbing areas, spaces to chill-out, pets, vegetable and flower gardens and a friendship bench. In terms of design, it is important to consider what the environment looks like from the child’s perspective, as this can be quite different to what it looks like from the adult’s perspective. When the play environment is designed according to adult selected themes and resources, it is unlikely that it will truly respond to children’s needs and interests (Rogers and Evans, 2008). The environment should be conceived as constantly evolving and children should be consulted with regarding their needs and preferences on an on-going basis. Collaborating with children around the design of their play environment and the selection of play materials ensures that materials reflect their authentic play interests (Trawick-Smith, Russell & Swaminathan, 2011). Consulting with children regarding their play environment is important in “guarding against ‘adulterating’ children’s play with adult agendas” (Lester and Russell, 2008, p.36).

3.3.5 Standard Eleven: The Child and Professional Practice

Practising in a professional manner requires that individuals have skills, knowledge, values and attitudes appropriate to their role and responsibility within the setting. In addition, it requires regular reflection upon practice and engagement in supported, ongoing professional development.

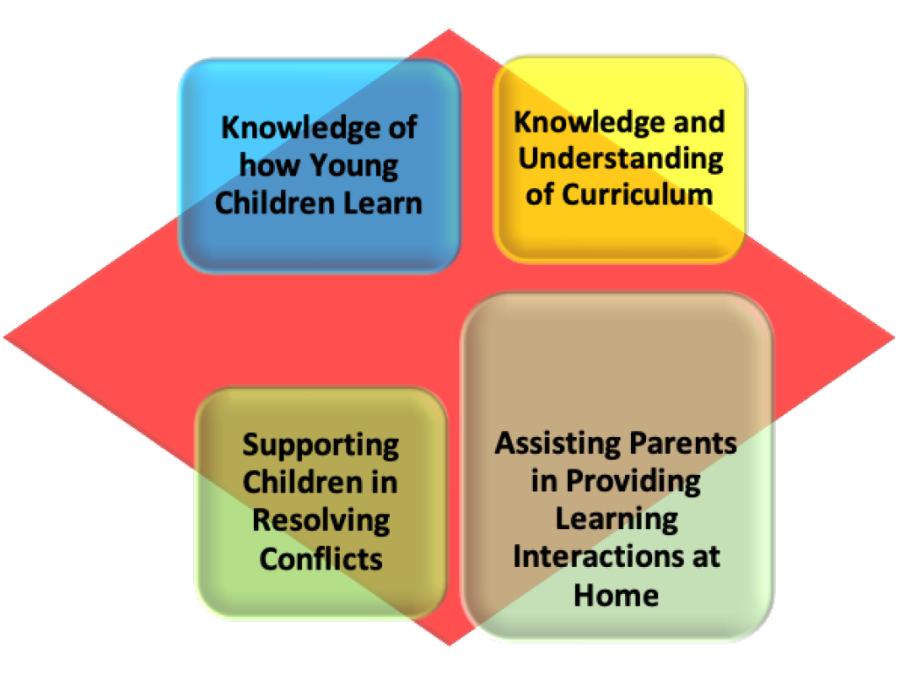

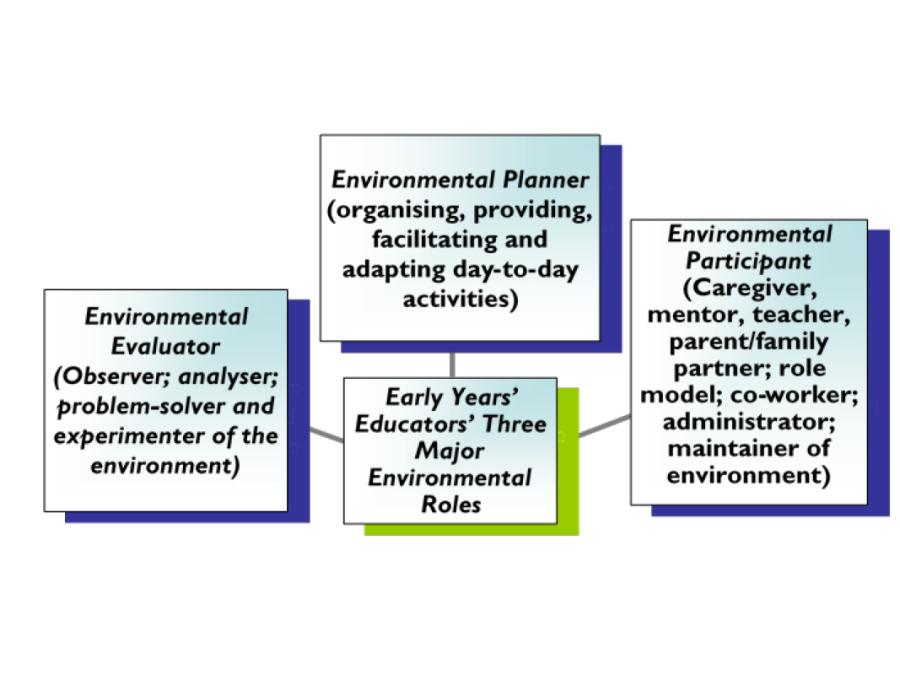

3.3.5a Quality in ELC